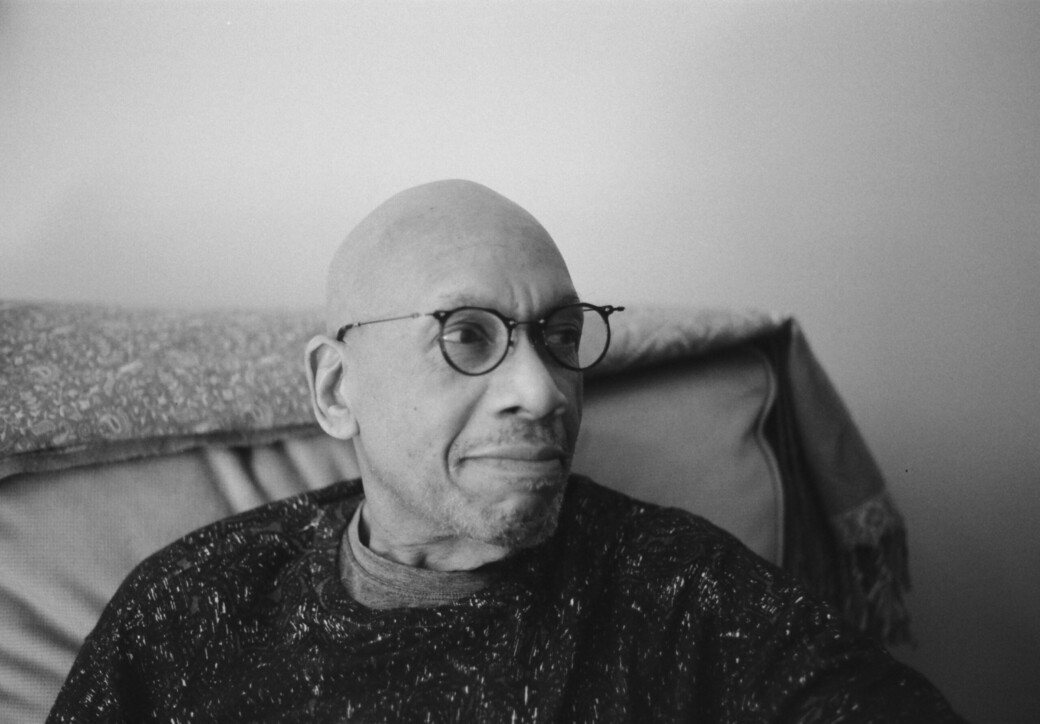

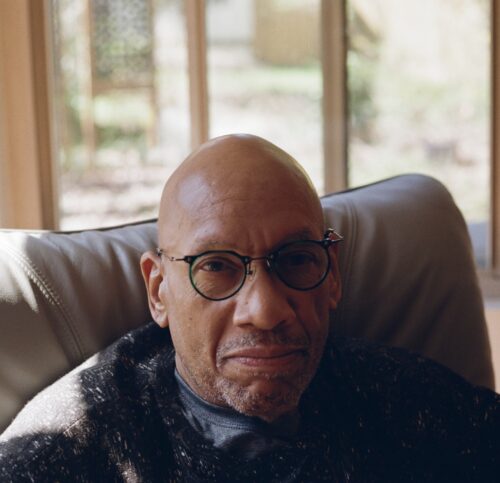

Willard Jenkins has been connecting jazz with listeners for more than 50 years. Now, he’s an N.E.A. Jazz Master.

Willard Jenkins wasn’t a jazz fan first. Growing up in 1960s Cleveland, naturally he loved the sounds of Motown and Stax and other soul records more than anything. But he heard that music a little differently — at least, differently from how it’s usually talked about.

“I was this odd kid,” Jenkins said in a recent interview. “I paid a certain attention to the instrumental aspects of those records. You know, I knew who James Jamerson was before any of my peers did.”

To him, soul music sounded like textures and feelings, rhythms and harmonies, much more than it sounded like simple hooks or memorable lines. Perched in front of his dad’s hi-fi system, the teenager’s ears were opened up by Jamerson’s clipped bass lines on Motown records; the screws and stabs of the JBs’ horns; the swelling strings under Sam Cooke’s voice on an RCA single.

Jenkins soon found his way to jazz, via his father’s record collection, and you could say his fate was sealed. In the 60 years since, he has followed a curious, discerning ear into a love affair with the music. And he’s insisted on sharing the love. Though never a musician himself, Jenkins has played just about every part there is in the off-stage ensemble responsible for connecting jazz with its audiences: journalist, author, disc jockey, festival director, nonprofit organizer, administrator.

At the Kennedy Center on Saturday, Jenkins, 75, will be awarded the Jazz Masters Fellowship by the National Endowment for the Arts, an honor given to just one non-musician per year.

He will have the added pleasure of accepting the award in his adopted hometown, the nation’s capital, where he has been an area resident for the past 35 years. Despite almost never being seen on a stage or under a spotlight, Jenkins has made profound impressions on the scene here — especially over the last nine years, serving as the artistic director of the DC Jazz Festival.

“I hope I’ve been a part of more people appreciating the music, appreciating the impact of the music, appreciating the origins of the music, in some way, shape or form,” he said. “That’s what all the different things that I’ve tried to do have been about, I guess you could say: proselytizing on behalf of the music. Because I’ve always recognized how under-recognized it is. And I’ve always felt like my biggest responsibility, the bottom line, has been about audience development.”

Jenkins on Saturday will receive the A.B. Spellman Jazz Masters Fellowship for Jazz Advocacy, a prize named in honor of another D.C.-based writer-turned-advocate, and a good friend of Jenkins’. The other recipients of the 2024 Jazz Masters award will be saxophonist Gary Bartz, pianist and organist Amina Claudine Myers, and trumpeter Terence Blanchard.

I spoke with Jenkins on a recent Sunday at the downtown studios of WPFW 89.3 FM, D.C.’s “jazz and justice” station, where he has held down a radio show since 1989, the year he arrived in D.C. Even now, he devotes the first hour of the show to classics that he can be sure listeners will love, and the second half to new releases, from across the broad territory of so-called jazz.

He treats radio programming as the art of modeling music appreciation. “I’m constantly taking notes about things that I hear and working on various combinations. Because the way I operate my radio program, I consider it doing sets. Two or three tunes in a row, or whatever the case may be,” he said. “It’s an opportunity for me to be on the air and to bring my sense of the music to a listening audience.”

Jenkins has made an equally profound impact on writers in the area. I can attest first-hand to the frequent experience of getting an email from Jenkins after he’s read something that you wrote. He makes a point of reaching out — whether his comments are full of praise or sharply critical, they rarely fail to point out another element that could’ve borne mention. The story is always a little deeper, he’s saying; there is always more to know.

Committed throughout his career to uplifting younger writers, especially Black writers, Jenkins is counted as a longtime mentor by such now-established critics as John Murph and Eugene Holley, without whom the landscape of music writing today would not be the same.

His current role at DC JazzFest seems like an ideal platform from which to evangelize — and to keep his open ears engaged. “Through his writings, and over 50 years of being involved in the music, he’s just learned so much about the nuances of jazz,” said Sunny Sumter, the executive director of DC JazzFest. “When we see what’s happening culturally, socially, the music is going to follow that. And I think Willard, even at the age that he is now, understands that. So he is willing to embrace that change.”

She added: “I said to him the other day, I don’t know many people your age that are still growing and still learning. And he is.”

Jenkins was in high school when he dove into his father’s jazz LP collection. “I started reading the liner notes,” he said. “It might be a piano player’s record, but then I might hear something from some of the other players that struck me, so I’d keep their names in mind. So the next time I went to the record store, ‘Well, let’s see if they have any records.’”

Some of the same names from the back of those albums were also being advertised at Leo’s Casino, where he spent formative Sunday afternoons attending soul music matinees for the under-18 crowd, but where jazz was often on at night. One day he watched the Temptations and the O’Jays duke it out at a Battle of the Bands; his eyes stayed trained on the instruments all the while.

By the time he headed to Kent State University in 1968, he had given himself a full 101 course on jazz history via the liner notes method. He became the go-to jazz head at his fraternity, Omega Psi Phi, and introduced his frat brothers to albums like Freddie Hubbard’s Red Clay and Chick Corea’s Return to Forever. Some nights he’d drag them out to the Smiling Dog Saloon, Cleveland’s major jazz club, for sets by the likes of Miles Davis and Sun Ra.

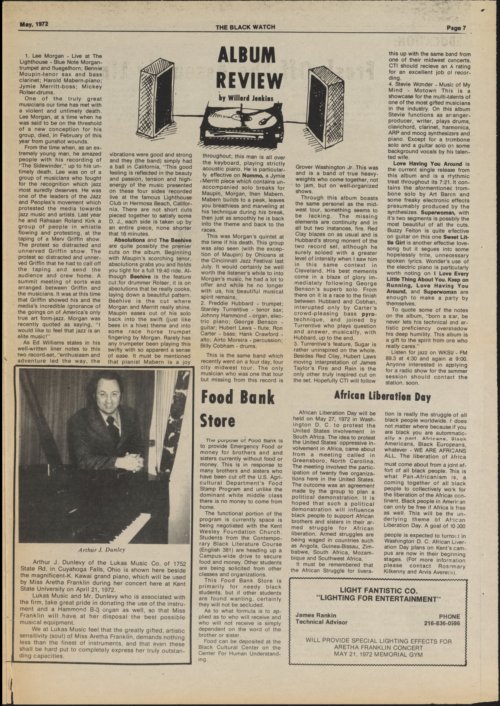

He started writing a “Jazz Reviews” column for Black Watch, a radical publication that had recently been founded on campus by a group of Black students. The stylistic spread of his reviews reflects how understandings of what “jazz” meant were shifting during that time, at least among young Black listeners: One March 1972 issue includes Jenkins’ takes on records by Billy Preston (I Wrote a Simple Song), Donny Hathaway (Live) and the Crusaders (Crusaders I). “A very satisfying, exciting package,” he wrote of the Crusaders’ first album without the word “Jazz” as part of their name. “Jazz or not this is a jive group.”

A couple months later, the column’s name too had changed, to “Album Review.” But the content remained focused on jazz and its close cousins: That May, he wrote up Lee Morgan’s Live at the Lighthouse (“grabs you and holds you tight”); CTI Records’ California Concert featuring Hubert Laws and Freddie Hubbard, et al (“something seems to be lacking”); and Stevie Wonder’s Music of My Mind (“a showcase for the multi-talents of one of the most gifted musicians in the industry”).

The start of the ‘70s was a moment that’s long been tagged as the death of jazz — when pure gold was melted down into an alloy. But Jenkins would push back on that. Like so many young listeners, especially his peers, he connected with Jimi Hendrix, Billy Preston, John McLaughlin and Herbie Hancock, all at the same time. Rather than calling this the end point of a pure genre, you could say he had arrived to Black American music in the moment when it was at its most unified. In the late 1960s and early ’70s it felt almost completely natural to embrace the full spectrum — from Jean Carne to Stanley Turrentine to the Art Ensemble of Chicago. (He has a particularly vivid memory of the Art Ensemble in those years: “The first time I saw their ensemble it was ‘full force,’ which meant they had brought all of their instrumentation, down to the toys,” he said. “They brought everything on this tour.”)

And he found that looking at the music through a cultural lens helped him evangelize. Because he’d turned his less music-obsessed friends on to stuff like Turrentine and Wes Montgomery, they gave the “outside” stuff a shot, too.

“I was writing as a means of [saying], ‘Here you go, this is what’s happening. This music is happening; here’s what’s going on, and who’s who,’” Jenkins said. “So I started writing record reviews, and lo and behold, certain companies started sending records to the Black Watch to be reviewed. I said, ‘Wow, this is interesting. You can actually get records from doing this.’ … The whole writing aspect just kind of grew. But it did begin as a sort of evangelism.”

After graduating from Kent State in 1973, he moved back to Cleveland, took over a friend’s radio show on WKSU, and started writing for small newspapers around town. When Miles Davis arrived that year for a run at the Smiling Dog, Jenkins and another budding writer managed to wrangle an interview from jazz’s most elusive figure. After staking him out at the club earlier in the week, they’d been told to show up at his hotel on Saturday afternoon. But when they did, they found themselves waiting for much of the afternoon in Davis’s road manager’s room, watching a football game on TV, feeling forgotten. They were about to leave and try again the next day. “We’re dejected. We stand up, and we go to the door,” Jenkins remembered. “I have my hand on the door knob, and all of a sudden I hear this voice: [rasping] ‘What y’all want to talk about?’”

What ensued was a candid two-hour back and forth with the Prince of Darkness. “He talked about a lot of stuff: boxing, women, music, all kinds of things,” Jenkins said.

Jenkins would parlay his alt-weekly bylines into regular contributions to the Cleveland Plain Dealer, but he resisted being categorized as simply a critic. He was an enthusiast first, an evangelist second — and as time went on, there would be an increasingly crowded tie for third. He started teaching jazz history courses at Cleveland State University, and in 1977 he joined up with a few friends and fellow fans to create the Northeast Ohio Jazz Society. Jenkins was its founding director. The little group started presenting jazz films and concerts around the area, bringing artists like Arthur Blythe and Bobby Hutcherson. By 1980, it was putting on the annual Tri-C Jazz Festival; Jenkins served as lead programmer.

Curating concerts and writing criticism seemed to go hand-in-hand for him. “It was an opportunity to bring people who I had only been writing about to the stage, and to get firsthand evidence,” he said of Tri-C. “And also to expose the community to firsthand evidence of these people’s artistry.”

In the mid-1980s, jazz was making its way back onto the national radar. A tie-dyed, electrified Miles Davis was on the scene again, after a six-year retirement; opposite him, Wynton Marsalis’s campaign for a new traditionalism was gathering steam. But it was a bold new world on the airwaves. Hip-hop was rising. Jazz-rock fusion had become overspent; arena rock was in. Smooth jazz was gobbling up radio market share and moving albums by the millions. So, what were serious listening audiences really hungry for? Would they still go to jazz clubs? Festivals? Was the music destined to survive only in concert halls, before elite audiences?

In the mid-’80s, Jenkins heard about a job opening that would allow him to start answering these questions, full-time. At the behest of the Great Lakes Arts Alliance, with funding from the N.E.A., Jenkins spent a full year bouncing around the Midwest in his car, conducting a needs assessment for the area’s jazz community, interviewing musicians, presenters, audience members, DJs, journalists and others in and around the jazz world.

The report he produced was well received, and its findings were clear: A love for the music was widespread, but so was a need for greater support. “The evidence was so compelling as far as the various needs … that Great Lakes Arts Alliance determined that they wanted to make it a full-fledged program,” he said. He moved to Minneapolis to take the reins of the first federally funded jazz service organization, based at Arts Midwest, where his staff put together the country’s first regional jazz database and he wrote a series of technical assistance booklets for musicians, presenters, educators and organizations.

While in Minneapolis, he tied the knot with his fiancée, Suzan, whom he had met in Cleveland, and to whom he’s still married almost 40 years later. “We got together on the platform of jazz,” he said, adding that their common love for the arts has stayed at the heart of their partnership. (Suzan Jenkins is currently the chief executive officer of the Montgomery County, Md., Arts and Humanities Council.)

In 1989, the couple moved again, to D.C., where Willard became founding director of the N.E.A.’s National Jazz Service Organization. There he helmed a multimillion-dollar budget and built a nationwide network of jazz presenters and regional arts groups.

And on the local front, Jenkins found himself welcomed by a jazz community that was greater, and more tight-knit, than anything he’d experienced. Soon enough, he was friends with people like Bill Warrell, the proprietor of the experimental performance venue DC Space; D. Antoinette Handy, the director of the N.E.A.’s music program; Tom Porter, who brought Jenkins into the fold at WPFW; Bill Brower, a journalist and advocate who played a huge behind-the-scenes role in D.C.’s jazz world; and Fred Foss, the saxophonist, flutist and educator. Porter invited Jenkins into the Listening Group, an exclusive circle that gathered regularly over the ensuing decades to talk about and listen to Black creative music.

Meanwhile, Jenkins kept up writing for publications like JazzTimes and DownBeat, and in the mid-2000s he began his own blog, Open Sky Jazz, on which he has posted hundreds of interviews, articles and more, to this day. Particularly important has been his series of interviews with fellow Black jazz writers, under the banner “Ain’t But a Few of Us,” in which he and his peers discuss the strange problematics of being minority commentators in their own, Black art form. In 2022, Jenkins released Ain’t But a Few of Us, the book, on Duke University Press. It collects many of these interviews and anthologizes a number of articles on jazz by Black writers.

On a 1992 trip to Trinidad, where he was reviewing a jazz festival, Jenkins befriended the flutist T.K. Blue. “My hotel room in Port au Spain was right next to their room, and I kept them awake incessantly with practicing,” Blue remembered. “Suzan said, ‘Man, who is that – I want to break his horn!’ Because I’m up practicing at 8 in the morning. We laughed about it years later.” In an Open Sky post from 2021, Jenkins is a bit gentler: “Each morning our room at the Trinidad Hilton was enhanced by the sounds of a flutist warming up nearby.”

But the friendship was a natural fit; Blue and Jenkins became close. “With Willard, I always felt that camaraderie,” Blue said. “And I was always very much attracted to his encyclopedic knowledge of the music. I don’t know anybody, quite honestly, who listens to as much live jazz as Willard Jenkins, unless it’s a club owner.” Blue has come to rely upon his friend to keep his ear to the ground. “You have a lot of folks who have what you call blinders on, where they only listen to one thing. But Willard’s ears are huge,” he said. “I talk to him, or see a text — ‘just heard so and so!’ I always appreciate it. He always comes up with different angles to promote the music.”

Through Blue, Jenkins also became close with the iconic pianist and composer Randy Weston, in whose band Blue played. Over a period of 10 years, Jenkins sat, talked, traveled and learned with Weston, joining him on tour in Morocco, Guadeloupe, Europe and around the United States. In 2010, they published Weston’s autobiography, African Rhythms. The cover of the book reads: “Composed by Randy Weston” and “Arranged by Willard Jenkins.”

In 2013, Jenkins was named a Jazz Hero by the Jazz Journalists Association. But when the artistic directorship of DC JazzFest opened up, Jenkins found he wasn’t interested in looking back. He took the job ahead of the 2015 festival, and is now approaching his 10th year in the role, where his deep knowledge and curious ears have helped establish the DC JazzFest as a top-tier music festival.

“I’m always interested in what a great master like Kenny Barron is doing,” he said. “But I’m also always interested in what a fantastic young person like Miho Hazama is doing — or these geniuses like Vijay Iyer. You know, I could go on.”

DC, DC jazz, DC Jazz Festival, DC JazzFest, jazz, Sunny Sumter, TK Blue, Washington, Willard Jenkins