Editor’s note: In recognition of Jazz Appreciation Month, CapitalBop is publishing a series of articles throughout April on books that depict the history and culture of D.C. jazz. This is the first piece in that series; you can read the second here and the third here.

There are 195 photos in the book Washington, DC, Jazz, part of the Images of America series, that tell a visual history of the jazz scene in the nation’s capital — and help to fit it into a century of jazz lore.

Co-written by Dr. Regennia Williams and the Rev. Dr. Sandra Butler-Truesdale, two historians and activists in the D.C. music community, the book depicts everything from the earliest contributions of Washingtonians to the Black music tradition, starting with military bandleaders like James Reese Europe, to performances by leading voices in the community, like Amy K. Bormet and Aaron Myers II.

In between, photos show Duke Ellington in his hometown; touring icons like Miles Davis; and D.C. musicians on the scene, like saxophonist Ron Holloway, shown alongside trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. Williams and Butler-Truesdale present a narrative that shows just how much jazz has meant to D.C., and D.C. to jazz. Seeing photos of locals like guitarist Paul Bollenback or the late saxophonist Buck Hill playing to huge crowds at downtown public events, one gets a look at a history that cannot be represented through text alone.

In a phone interview, Butler-Truesdale explained that one of the basic goals in assembling the book was to choose photos that would personalize readers’ relationships with the musicians. We talked about how she and Williams went about that, how the project began, and her favorite images from the book. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Joshua Redman (left) and Buck Hill lead a Duke Ellington birthday concert in downtown Washington, D.C. in 1992. Sir Roland Hanna (piano), Steve Novosel (bass) and Warren Shadd (drums) fill out the band. Courtesy Michael Wilderman/jazzvisionsphotos.com

CapitalBop: What were the main inspirations for making the Images of America Washington, DC, Jazz book?

Sandra Butler-Truesdale: Well, one of the things is that, for the most part, musicians who are from the DMV, and particularly from Washington, D.C., are not often recognized. People and great musicians come here and they pick our musicians off, perhaps for recording sessions or to travel and tour, and sometimes musicians go and play with them for a long time, but they still are not recognized — and not recognized as D.C. musicians.

So, the other thing that inspired me was that I had been, for a long time, wanting to document this wonderful history that we have, which is so important. I noticed that — at that time I was working on it — there wasn’t more than one book that sort of pointed to it, and it wasn’t about D.C. musicians. And I wanted to do this for a long time because the history of Washington, D.C., as far as music and theater is concerned, is really important.

CB: Why was important to capture that history in photographs — to do a visual history as opposed to, say a more written book?

SBT: Well you know, people in this time don’t read anymore; they don’t read a lot of text. So, it came to me that it would be better if we had pictures. People feel as ease to look at pictures and they can identify with that person and sometimes they’ll sort of, kind of remember, “Oh yeah! I saw that person in concert.” So, we give the names and sometimes the brief history. For instance, there are only a couple of them that are focused on Ron Holloway, he may have two or three pages, but I wanted them to be able to see and identify their associations with this or that musician. The Howard Theatre … the Casbah, the [Bohemian] Caverns, the Hollywood are small places where we went to see great musicians, many of them from Washington, D.C. — and Twins as well, as time went on. So, once again, I wanted our older population to be able to remember and identify, “Oh! That guy used to live next door to me! Marvin Gaye went to school with me,” you know, that kind of thing! And it’s personalized when you see the images, if that makes sense to you.

CB: And there are photos of musicians from outside D.C., but it strikes me that you also wanted to represent how D.C. was a center of the jazz world at that time.

SBT: Absolutely! There are other musicians there but, once again, the pictures of those musicians and even those musicians who are historic like John Philip Sousa, it still gives a certain pride and almost gives you a relationship with that person. If anybody was like me as a child, 4 or 5 years old, my grandfather was a march man: he loved John Philip Sousa! That’s what we heard in our house. So, I can identify with seeing John Philip Sousa. Buck Hill was a good friend of my cousin’s, so I can identify with him; and it goes on and on and on. People who, you know, go, “Oh, I’ve heard his name before but oh! There’s a picture of him, I remember seeing him!” So, it begins almost like a personal relationship.

CB: What was the process like of gathering all the images you include in the book, of choosing the ones you wanted?

SBT: Some of them came from the Smithsonian — John Hasse was a great help; Dr. [Fred] Irby up at Howard University; Dr. Williams, Reginnia Williams, did a lot of research at the Library of Congress as well. She came up with a lot of the photos in those institutions that we went to. Once we had the layout of the photos, we chose the ones we thought where — again, the word “personal” comes out — people would have a personal relationship, even if they [the subjects] weren’t actually living in Washington, D.C., even if they weren’t from here. Of course, you know that many musicians were not born here or may not have been natives, but many of them came here — they liked Washington, D.C., they moved to Washington, D.C. (Now, with gentrification, many of them have had to move out of D.C. to the suburbs because they can’t afford to live here.) That’s more or less how we did it. Let me just say that John Hasse and Dr. Irby were a great help.

CB: Did you set out knowing what artists and institutions you wanted to cover? How did you decide on who to include?

SBT: Duke Ellington, of course, was one of the key musicians. However, Buck Hill, who I had a really good relationship with, and Ron Holloway, being a native Washingtonian and well-traveled and involved with many musicians playing several genres of music, were ones I picked. But I pulled out a lot of musicians who played as studio musicians or musicians who played with different groups that were popular and people may not know exactly who they are. That’s how I chose some of them.

CB: Were there any photographs that you wanted to get but couldn’t? Any you could not get the permissions for?

SBT: Yes, and there were several for whom we could not get permission or did not want to participate or wanted to be paid to have their photographs in the book. Michael Wilderman and Lawrence Randall had a lot of photographs … Lawrence did a lot of the photography right out of [the] scene. People who I didn’t have photos of: He would go where they were playing and photograph them. The other thing, too, is that some of those photos were in the public domain.

CB: You talked about how the photos needed to evoke some kind of personal relationship. Was there ever debate or discussion on the musicians playing live versus some of the more staged/portrait photos? Did it depend on what best contextualized the artist?

SBT: There was not a debate. During the time of putting this book together, we worked very closely with each other and fortunately we had some of the same ideas about how the book should be published. We also knew that Blair Ruble and a couple other people were writing a book that had a similar name; we knew it was going to be very detailed. That played the decision on how we wrote this book.

But to answer your question, it depended on the artist. The other part of that is that we wanted to show some of the musicians actually playing and being in more historical settings to see how far back they went. But then we wanted to have some of them — like these musicians at the Southwest Waterfront — we wanted it to be like … with some of these musicians like Greg Gaskins and others, it gave a reflection of Washington, D.C. itself along with the photos of the musicians.

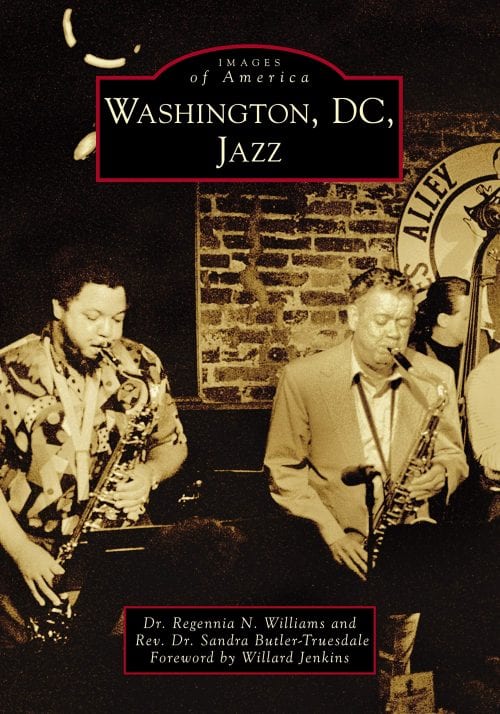

The cover image to ‘Washington, DC, Jazz,’ part of the Images of America series, depicts saxophonists Ron Holloway and Buck Hill at Blues Alley. Courtesy Arcadia Publishing

CB: Do you have a favorite photo in the book?

SBT: My most favorite photo is the cover with Ron Holloway playing with Buck Hill. They’re both very unique personalities. I like, and this is very personal, Buck Hill’s dedication to his family: the fact that he could have left town to go on the road with such musicians as Miles Davis … he loved his family so much that he decided to stay here and work at the post office. Who does that?

Ron Holloway is a person I’ve known for many years. He played with the El Corols, which was the first young band in Washington, D.C., and this gentleman has chosen to play almost every genre you can think of. A lot of people say he’s not a jazz musician because he does that, but he’s one of the workingest musicians in the metropolitan area and he’s called from all over the world to come and play. This man has a character that’s unbelievable. He’s dedicated to his music, he was dedicated to his parents, and he’s dedicated to this city! I also like that we have one of the historical venues, Blues Alley, in the background. That’s top of the line stuff! ![]()

Join the Conversation →