Two months after social-distancing measures shuttered the workplaces of thousands of performing artists in and around D.C., many local musicians have been unable to access any form of government financial relief.

Even after federal law recently required the District, Maryland and Virginia to offer unemployment insurance to self-employed workers, area jazz musicians’ experiences have largely proved the same: long waits, confusion and no economic aid.

The CARES Act, the $2 trillion federal relief package passed in late March, mandates that self-employed workers be included in state unemployment programs through a provision called Pandemic Unemployment Assistance. PUA bolsters those programs’ funding, ensuring that individuals would receive, at minimum, $600 per week in relief for up to 39 weeks.

But state and city labor offices remain backed up, with over 38 million jobless claims filed nationwide since the start of the coronavirus pandemic. And more than a month after the PUA was rolled out, none of the more than 30 working musicians that CapitalBop contacted said they had received funds from their respective state or city unemployment programs. Just two of those musicians reported being accepted into such a program.

Freelance musicians living in Maryland reported particular frustration with the state’s online unemployment relief portal, known as BEACON. When it launched on April 24, the website experienced extreme delays as hundreds of thousands of people attempted to apply. Drummer Ele Rubenstein, 30, of Takoma Park, Md., said the site “instantly fell apart” when he tried to access it that evening.

Despite a pledge from Gov. Larry Hogan to quickly address the tech issues, BEACON’s problems have persisted. Saxophonist Lionel Lyles, 42, who lives in Baltimore, said he initially got stuck in “a virtual wait line,” where he needed to continually monitor his computer, waiting until the nearly 100,000 people ahead of him had gone through the process. After four days of trying and failing to submit his application, Lyles said that he was able to submit his claim after spending six and a half hours on the site in one sitting. Lyles and one other musician in a similar situation both said there was no word on how quick the turnaround would be.

“Have I gotten the funds? No,” Lyles said. “Do I know anything that’s going to happen after? No, I don’t. But I can say that as a private contractor, as a self-employed musician who does other things as well as performing and playing, it’s been a nerve-wracking and very stressful time not knowing when everything will be made available to me.”

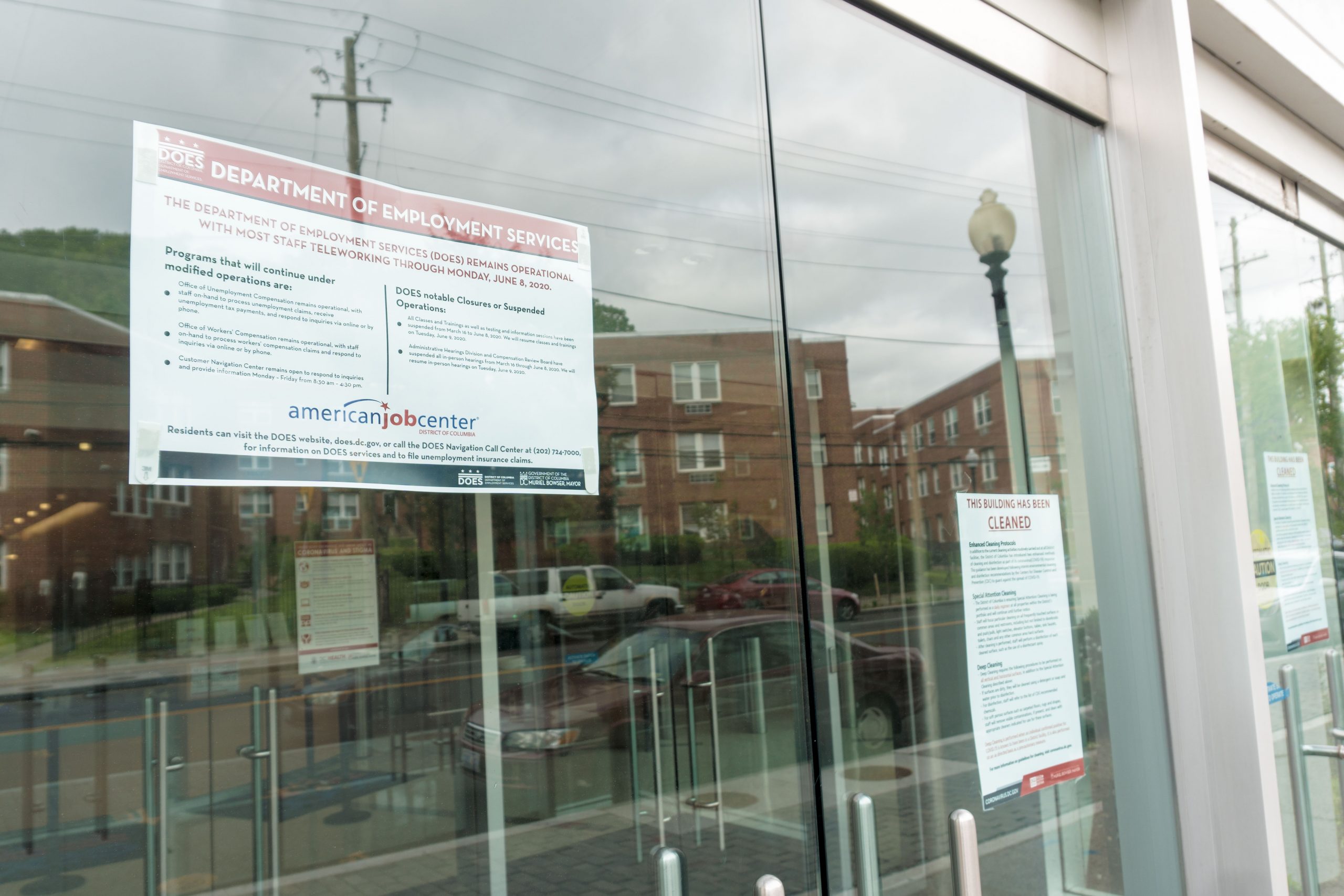

Those living within D.C.’s borders haven’t reported much more success with the District’s online relief portal, administered by the Department of Employment Services (DOES).

Both Pete Muldoon, 43, and Steve Arnold, 24, told CapitalBop that their applications for unemployment insurance were rejected on the same day that they filed. Muldoon, a guitarist who has spent the last 20 years working and living in D.C., said that he received a letter shortly after he was denied unemployment stating that the process was going to be halted so his identity could be verified; he hasn’t heard from DOES since.

Arnold said that after applying for relief and being rejected in early April, he has found himself stuck in a cycle of having to repeatedly submit a continued claims form to keep his application alive — all while not knowing when exactly he will be paid.

This has forced him to make difficult choices. He has temporarily moved in again with family, although he still pays rent for his own room in a group house in Northwest D.C. Recently, he was offered a gig in Baltimore as part of An Die Musik’s donation-based livestream series, where pay has reached up to $200 per artist. For Arnold, every little bit now counts; he said he had lost at least 42 gigs and thousands of dollars in income since the pandemic began. But taking the gig would increase the risk of coronavirus exposure and transmission to his family members, including his 96-year-old grandmother. Ultimately, Arnold said he chose to play the show. “I haven’t not had a gig in a given week in maybe four years,” he said. This was a chance to get back to work, he said, if only for a night.

An informational sheet is posted on the door to a D.C. government building on Minnesota Avenue SE. Jamie Sandel/CapitalBop

In Virginia, the situation is similarly unclear. While an April 14 memo from the Virginia Employment Commission declared that self-employed workers such as freelance musicians would be eligible for unemployment benefits, it was not clear how they would be able to apply. When the functionality was released, it required that PUA seekers apply for and be rejected by the state’s traditional unemployment program before submitting a second, separate application.

Three Virginia musicians that CapitalBop conducted in-depth interviews with had not yet applied for government funding, citing confusion about the process.

Joe Herrera, a 41-year-old trumpeter who has lived in Northern Virginia for 12 years, said that rather than constantly scrambling for relief funding, his time is better spent “putting my efforts towards [virtual] projects, that I know I’m going to get [paid for] from whatever producer or whatever artists I’m working for,” he said. “I’m putting my time and effort into that right now, more than I am trying to chase down some money that I might get through some bureaucracy.”

Jack Kilby, 30, an Alexandria, Va. native who has established himself as both a drummer and a record producer at his home studio, Crab Shack Music, chalks up the inability of local musicians to secure financial relief to a simple lack of manpower. “The problem is, we’re all a small business team of one,” Kilby said. Without a “whole team of people” dedicated to fundraising, as institutions often have, Kilby said that the process for a lone musician to actually figure out how to acquire money through PUA programs just isn’t “going to be worth the time.”

When asked about the difficulty musicians were having applying for PUA funding, Joyce Fogg, the communications manager for the Virginia Employment Commission, attributed it to system overload. She noted that over 100,000 Virginians have applied for PUA benefits. “We’ve been inundated,” Fogg said.

Fogg acknowledged that the process may seem “cumbersome,” but advised musicians to apply nonetheless. “Don’t just sit there and say, ‘Well, am I eligible or not?’” she said. “Go ahead and apply, and we have people who look at that and determine whether you’re eligible or not. You may think you’re not, and you are.”

CapitalBop also reached out to spokespeople from both the Maryland Department of Labor and the D.C. Department of Employment Services, both of which are responsible for the administration of PUA funding. Neither responded to multiple requests for comment over a series of days.

I can say that as a private contractor, as a self-employed musician who does other things as well as performing and playing, it’s been a nerve-wracking and very stressful time not knowing when everything will be made available to me.

Lionel Lyles, Maryland saxophonist

Both Maryland’s and D.C.’s publicly funded arts councils also announced emergency grants for artists. The Maryland State Arts Council’s Emergency Grant ended up awarding 30 independent artists a total of $130,682, according to its website, but it closed for applications on May 5, apparently for the duration of fiscal year 2020. In the District, a D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities (DCCAH) program promised a one-time, no-strings attached grant of $2,500 to adult residents of D.C. that the commission determined to have been adversely affected by the pandemic, according to the grant application’s guidelines. The turnaround time for this grant was speedy — applications were accepted between May 11 and May 15 — and the number of grants doled out by DCCAH will be limited by the amount of funding allocated by the National Endowment for the Arts. That number is not publicly available; the commission did not respond to an interview request from CapitalBop.

In all, CapitalBop conducted in-depth interviews for this article with nine musicians, and surveyed over 30 in all. None have actually received any PUA payments, and many recounted similar experiences of delay, confusion, misinformation or denial. Their experiences with private benevolent funding have not been much better.

Many musicians have tried to look beyond the PUA, to private nonprofits and other charitable sources. The list of private relief funds is expansive, and includes local efforts like the DC Jazz Musicians Benevolence Fund, run by Westminster Baptist Church; regional efforts like the Artist Relief Tree (ART); and national efforts including the Grammys’ MusiCares COVID-19 Relief Fund. Several organizations, including CapitalBop and national publications such as Billboard, have compiled these resources into manageable lists.

No matter whether publicly backed or privately run, almost all of these one-time, short-term sources of funding have been overwhelmed with applications. For example, the Artist Relief Tree, which raised hundreds of thousands of dollars within the first weeks of the pandemic, had a 5,500-person waiting list by mid-April, according to The New York Times.

The musicians CapitalBop spoke to reported little success in acquiring funding through private donations. One musician, who asked not to be identified, reported applying to upwards of 50 private sources of financial relief and receiving funds from only one.

Many of the artists interviewed hadn’t applied, saying the payouts did not seem worth the effort, or citing an impulse toward altruism. Multiple musicians shared Herrera’s feeling of not wanting to “take money from the coffers [of relief funds] when [that money] might be able to go to someone that actually might need it more than I do right now.”

Simone Baron, a 30-year-old multi-instrumentalist based in D.C., expressed similar sentiments. Noting that her attitude in “normal” circumstances is to apply to as many grants as she can, she is currently trying to free up resources for others to apply. “I haven’t felt totally comfortable about applying for things right now,” Baron said. “I actually submitted an application for one grant and I felt like I regretted it afterwards.… I feel that even though it’s up to them to decide whether I get it or not, at the same time, that’s one more person that they have to look through.… They should really only be getting applications from the people that need it the most, and distributing resources appropriately.”

The pitfalls of non-governmental funding makes the PUA that much more appealing: a guaranteed, steady income, from a seemingly unlimited supplier of cash in the federal government. However, the application process has created a barrier to entry that simply appears to be too high for many members of the D.C. region’s jazz community. ![]()

Join the Conversation →