Remembering Aaron Martin Jr., a saxophonist with an unending commitment to the music

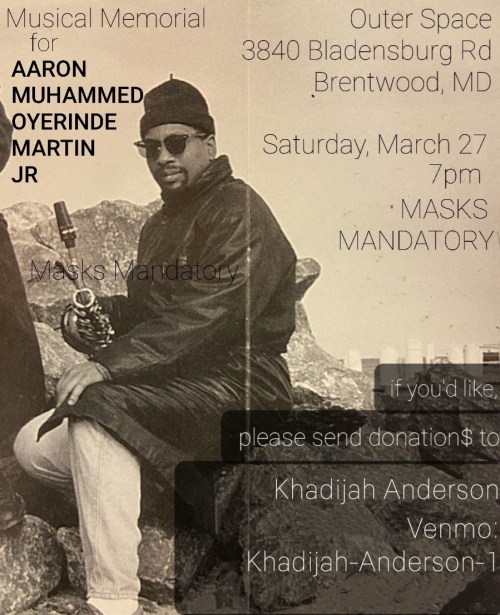

Editor’s note: Aaron Martin, a saxophonist who had been an important part of the D.C. jazz scene for decades and served as a mentor to all of us at CapitalBop, died on March 18. A memorial concert will be held in celebration of his life this Saturday, March 27, at 7 p.m. Details on that show are available at the bottom of this page, or at this link. His family is accepting donations via Venmo to defray homegoing-related costs, at Khadijah-Anderson-1.

Aaron Martin Jr. had no cut cards. He was quick to correct, but also quick to adjust himself. The phrase “no bullshit” falls short of describing the strength of his personality. He commanded respect, fought bitterly against ignorance of any kind, and did so always with the utmost generosity and humility. On many occasions he would famously let someone know what books they should have read, what music they should have listened to, what important figures they should know. He had very strong standards for those around him, for it was the same level of discipline and know-how that he demanded from himself.

Aaron Martin Jr. is the most dedicated musician I know. In our time together, I have never seen anyone who spent as much time practicing as he. By the time we got together, his practice regimen was already legendary. Older musicians and community members in D.C. recalled hearing him practice downtown during his lunch hour, and after work. He often spoke about his practice haunts behind the Giant in the Brentwood area of Northeast D.C., then on the steps of an abandoned industrial building along Brentwood Road. Day or night, no matter the weather, he could be found wailing with focus for hours on end.

Eventually, as we became close friends and collaborators, we rented our own practice room at Goldleaf Studios. It was around this time that he finally was able to retire from his office job downtown, and he was ecstatic at finally having the opportunity to devote his entire day to practicing the saxophone. The legend of his work ethic grew within the young, hip music community of Goldleaf, as he could be heard playing the same patterns over and over, the metronome volume on maximum. Already the elder of the famed art space, he also became known as its hardest worker. That dedication was inspirational to everyone in the space, some of whom would go on to some success, no doubt partially indebted to Aaron’s work ethic.

When we moved our practice space to Union Arts, the legend was fully formed, and he was at the height of his musical power. He would often remark that he was in the best playing shape of his life. Yet he would still fill the space with the sound of his constant practice regimen, often even sleeping in the practice room. Whenever he was seen out on the scene, always with his saxophone strap still around his neck, his mantra was often, “I gotta go get my time in.” He longed for the practice room, he longed to always strive and get better. Even though he was a senior citizen, fully formed in his powerfully unique sound and approach to the alto saxophone, he continued to push himself further.

Aaron Martin Jr. had a sound on the alto saxophone that sounded like no one else but him. To the jazz ear, it could be a fusion of Jackie McLean with Jimmy Lyons, Marion Brown with James Moody. To anyone listening closely, it is just him. His tone is distinctive, a school of alto playing that is becoming more and more rare. In the D.C. area he was so often relegated to the “avant garde,” sometimes in good faith and honor, oftentimes to mock and dismiss. However, he proved through his originality on the horn and his respect for the history of the Music that whatever you called his approach, his was just as potent and important as any other. Indeed, the legacy of the alto saxophone in general has a champion in Aaron Martin. He achieved the ultimate goal of discovering one’s own originality and personality on the instrument, and should be recognized as one of the last of a great generation of alto players.

Aaron Martin practicing at Union Arts. Courtesy Eli Fosl

He never stopped searching for mentors. As an elder himself, he started studying with D.C.-area mentor Fred Foss. To anyone observing, it would seem that Fred would be Aaron’s peer, rather than someone with whom he would study. His deep humility, however, kept him grounded in the idea that he could and needed to keep getting better, continuing to explore and discover himself on the instrument. He also wanted to show and prove that he was indeed an important saxophonist, especially for the D.C. area, and that he could and certainly did mentor so many musicians in the region and around the world. While he was studying with Foss, more and more musicians had begun to discover and appreciate Aaron. People were beginning to travel more to study and play with him, and he was being invited to perform with admirers all over the world.

Aaron Martin Jr. loved his family. He loved his daughter. Upon meeting him the conversation would likely shift somewhere along the way to the pride he had for his daughter. He generously gave perspective as a single Black father raising a daughter in Washington, D.C. — the joys and the struggles. He sacrificed his shot at an artist’s life abroad, rather than join the movement of musicians to Europe, where respect and recognition was seemingly more possible for someone like him. He was personally approached by Sun Ra to join his band, but his dedication as a parent was his priority, while music was his passion. Still, through his powerful reputation in D.C., he was invited to collaborate with the greats of his day, with his peers. He went shared stages with Jimmy Lyons and Anthony Braxton, Marshall Allen and Sonny Simmons, and many more luminaries, absorbing their energy and knowledge, sharing respect for one another. For despite its reputation as a heavily straight-ahead town, D.C. was still a hotbed for Creative Music activity, and he would successfully navigate the worlds of fatherhood and musicianship, eventually becoming a respected elder statesman of the community.

Aaron Martin Jr. loved baseball. He loved to talk about baseball. His practice sessions would often be supplemented with play-by-play of the game, coming through a radio. He was a lifelong fan, an embodiment of the romantic pairing of jazz and baseball. They are two pillars of the American artistic and athletic pantheon that teach about life and supplement each other. When at a baseball game he talked about jazz. When in the practice room or at a concert, he talked about baseball.

He loved Soul music, the sounds of Motown. He is a Mackin Trojan (a running pun on his high school’s mascot). He is a child of the 1960s in D.C., the height of the cultural revolution in Black popular music, where the Howard Theater would host its famous Motown Revues, turning on a whole generation of Macks and Divas. He was a soldier, like many of his generation who were sent to war. He was a dog handler in Korea, being spared the bloodbath in the jungles of Vietnam, yet he saw active combat nevertheless. He came home to his city on fire in 1968, his generation changed by the flames of war and revolution.

Aaron Martin Jr. is a revolutionary intellectual. He was part of the powerful awakening of Pan-African thought and culture that exploded in the Black power era and afterward, a movement that was arguably centered in Washington, D.C. He was deeply involved in revolutionary struggles for Black empowerment spiritually and politically. Depending on when you had met him, you might know him as Muhammad, due to his conversion to Islam as part of the movement for Black spiritual liberation. You might know him as Oyerinde, from his association with the Pan-African community. He was involved with the strong Black intellectual movement in D.C., absorbing the energy and knowledge of the community, contributing as a strong activist and organizer. He was also a person who actually read all the books and challenged those around him to be at least as up-to-date as he.

Aaron Martin Jr. has been the underlying spirit of CapitalBop and much of the movement we have been able to promote, present and preserve. He was part of the very first DC Jazz Loft at Red Door and has been an integral figure throughout our existence as an organization. He is the embodiment of what we have tried to support, the legacy of D.C.-based Black Revolutionary Music, specifically in Jazz. He is a trusted member of our community providing assured guidance in our presentations, always challenging us in our presentations. His perspective and voice are important in his encyclopedic historical memory of the era and spirit we wish to preserve. He has kept it alive and continues to inspire those he touched: in the mind, the Music, and in life.

Aaron Martin, alto saxophone, avant-garde, DC, DC jazz, free jazz, jazz, Washington