For nearly 40 years, The Left Bank Jazz Society (LBJS) presented regular Sunday jazz shows in Baltimore, and turned Charm City into a favorite destination for many of the East Coast’s best musicians.

Now, a trio of archival releases is shining a light on that history. New albums featuring performances by Sonny Stitt, Shirley Scott and Walter Bishop, Jr. are evidence of the bright moments that were fostered in those years by the LBJS, which brought together stellar musicians and a devoted audience during a period when jazz nationwide was thought to be on the wane.

Founded in 1964, the LBJS was created by a group of 13 jazz fans as a successor organization to the Interracial Jazz Society, which was founded in the 1950s to promote the music and help break down the racial barriers that were pervasive in Baltimore jazz clubs at the time.

“We just felt like there wasn’t enough live music going on in town,” John Fowler told CapitalBop. A founding member of the society, Fowler recalled that at the time the commercial district around Baltimore’s Pennsylvania Avenue – where many of the restaurants, bars and clubs that catered to Black audiences and featured the name Black artists were – had begun to decline.

The group came about when a group of devotees with a similar feeling convened one night in 1964. From there “came the idea of forming an organization devoted to perpetuating and permeating an awareness of jazz as an art form through organized activities such as lectures, concerts, sessions and field trips to festivals and nightclubs where jazz is featured,” as explained in the society’s 1975 yearbook.

The LBJS began hosting weekly concerts on most Sundays, featuring talent from up and down the East Coast. According to librarian and researcher Michael Fitzgerald, who has done his best to catalog every Left Bank show, the first took place on Sunday, Aug. 16, 1964, with the drummer Donald Bailey leading a quartet at the Ahlo Club.

According to Bertrand Uberall, a jazz researcher based in Washington, D.C., the name is said to have grown out of the founding members’ idolization of the left bank of the Seine River in Paris, where the cafés and bistros were known in the post-war years as a hot spot for jazz and intellectual debate.

Fowler, who served on the LBJS entertainment committee and would later be the body’s vice president and president, summed up the organization as “a group of people who loved music, who didn’t mind doing a little work … to be able to stand back on Sunday and say, ‘Hey man, I had a hand in this great concert that’s going on’.” Members collectively took up responsibilities more commonly shouldered by traditional presenting organizations or promoters: bringing designs to the printers, picking up fliers, making sure all i’s were dotted and t’s crossed on logistics, and then serving as the production crew and front-of-house staff at the Sunday shows.

In its first year of presenting, LBJS mostly stuck to more local or lesser-known acts like Gary Bartz and Buck Hill at the Alho, but did present Dizzy Gillespie at the Famous Ballroom in December 1964 as its first major “out of town” headliner. The group then quickly picked up steam and began presenting the likes of Jimmy Heath regularly (nearly monthly in 1965), the Jazz Crusaders, and soon-to-be-titans of the music like Herbie Hancock, Archie Shepp, Graham Moncur, Kenny Burrell, Art Blakey, and Elvin Jones (whose 1966 headlining date featured a young Abdullah Ibrahim).

LBJS’s presence was such that it even famously hosted John Coltrane for the saxophonist’s final public performance in May 1967. It was also around that time that the society found its longest-standing home at Baltimore’s Famous Ballroom, which would house the group’s concerts for its golden period over the next nearly-20 years.

The Famous Ballroom was an ideal location, not least due to the fact that it was located only two blocks from Baltimore’s Penn Station. Musicians coming down from New York could take the train down and back the same day, and would not have to lug their equipment around the city. Plus, the LBJS made the ballroom as welcoming an environment as possible.

“Man, it was a great thing down there,” Fowler recalled. “They had tables full of food, tables full of free booze, a really hip audience.… We even had a lady who sold cakes and pies and cookies and that kind of stuff.… We had a guy who cooked food for those who didn’t want to bring their own food, but theoretically you could bring everything you needed with you.… And nobody left town without their money, which I understand from musicians was kind of unheard of.”

Soon, musicians and bookers up and down the East Coast “had heard about the Left Bank because once the word got back to New York that there was a viable room that paid decent money, everybody was talking about it,” said Michael Cherigo, a Baltimore-based booking agent who has been in business since the 1970s. “It got around New York that it was happening in Baltimore, on that particular day – Sunday.”

Once musicians knew that there was not only a listening audience in Baltimore, but a gig that could also be quite the hang, Left Bank didn’t need to chase down artists. “For example, Wynton and Branford [Marsalis], we booked them when they were getting ready to leave Art Blakey’s band. They told us they were about to go out on their own, so we said, ‘As soon as you guys get your band together, give us a call,’” Fowler remembered. “All of a sudden, folks started calling and saying, ‘Hey man, I got a new group. Can I come down and bring my own group?’”

At the same time, the Left Bank was still trying to serve Baltimore’s own music scene as best it could, bringing in local groups to headline or play during intermissions — Pieces of a Dream got its start at the Left Bank doing just that, playing when they were still teenagers — as well as offering local bookers the chance to work with them.

Cherigo got into the booking business while a member of the society, when he booked trumpeter Ted Curson’s Quintet. He would go on to bring musicians like Dave Holland, Dave Liebman and Jack DeJohnette’s Special Edition to Baltimore. “Everybody came through because it was an off night,” Cherigo explained. “A lot of people would be playing Friday and Saturday in Washington and then they’d have Sunday between 5:00 and 9:00 p.m. [at Left Bank] and the gig was over at nine and they’d be on their way back to New York. It worked perfectly. I did a couple shows like that.”

LBJS’s energy began to wind down as audiences got harder to predict through the ‘80s, ‘90s and early aughts, but Fowler said they still could pack the house for a few acts. Regular crowd pleasers like Horace Silver, Blakey and Shirley Scott would still draw good numbers, even after the LBJS had to abandon the Famous Ballroom in the mid-80s.

However, these few sell-outs were becoming scarcer by the turn of the millennium, and with younger musicians asking for money the society could not pay, the LBJS closed up shop in 2002. Its final presentation was a concert by the Sun Ra Arkestra that was attended by 150 patrons; the LBJS had needed double that number to break even.

It had been almost 20 years since that final LBJS show when, in 2021, contemporary jazz listeners got a reminder of just how powerful those concerts had been: That’s when Reel to Real Records released Understanding, an LP featuring the powerful avant-garde drummer Roy Brooks leading an all-star quintet in a performance at the Famous Ballroom in 1970.

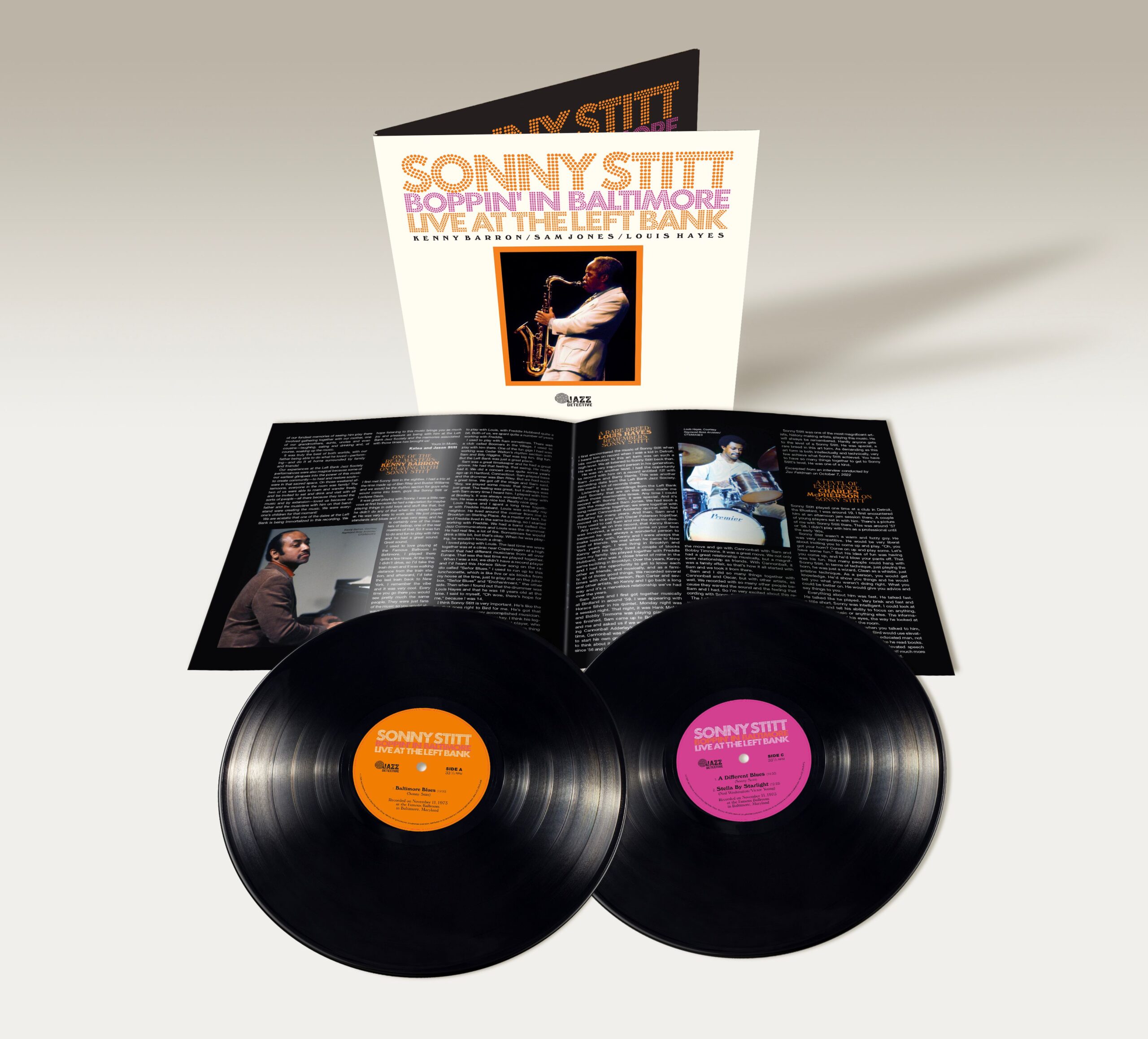

And now, a trio of similarly spellbinding albums will drive the point home further: Boppin’ In Baltimore: Live at the Left Bank by Sonny Stitt (recorded in 1973), Queen Talk: Live at the Left Bank by Shirley Scott (recorded in 1972), and Bish at the Bank: Live in Baltimore by Walter Bishop, Jr. (recorded in 1967). The former two were shows at the Famous Ballroom; Bishop’s performance was at the Madison Club. All three came out on vinyl last Saturday for Record Store Day; the Stitt LP was also released digitally worldwide that day, and the Scott and Bishop records are due for digital release this week.

Left Bank Jazz Society: 1975 Yearbook by jackson sinnenberg on Scribd

These three LPs were produced by Montgomery County, Md., native Zev Feldman, an award-winning jazz archivist and producer, who runs or works with several labels devoted to the revival of lost-and-found jazz recordings. The Stitt release is out on Feldman’s own Jazz Detective label while the other two are out on Reel to Real, which is run by Cory Weeds. (Feldman and Weeds also co-produced the Roy Brooks album.)

The music on these new LPs is drawn from a vast treasure trove of recordings made from the organization’s 1,000-plus concerts. Founding LBJS member Vernon Welsh taped nearly every concert he could during the years he was active with the Left Bank, so long as the artist consented. Fowler estimated that Welsh had taped around 250 tapes in total.

Originally, the tapes were made simply to allow Left Bank members to listen back and enjoy the music at a later date, since they were often too busy during the shows to listen live. However, Welsh also gave copies of the tapes to some artists, who would later commercially release them. According to Uberall’s research, there are at least 25 commercial recordings of Left Bank shows that have been officially released.

Feldman began working with Fowler and the Left Bank around seven years ago, after receiving recommendations from Uberall and Joe Lee, the namesake of Silver Spring’s Joe’s Record Paradise. Although he and Weeds have put out Left Bank records before, Feldman considers this upcoming trio of releases “a major crowning achievement,” partly due to the quality of the performances.

“I wanted to put all three out at the same time because I wanted to draw more attention to the history of the Left Bank,” Feldman told CapitalBop. “I wanted this to be an event. The Baltimore Left Bank reached all corners of the world…. I think it’s a really important organization and a part of our history. And the fact that these documents exist is just astounding, and really wonderful.”

In the liner notes to Boppin’ in Baltimore, Sonny Stitt’s children — Katea Stitt, the program director at WPFW 89.3 FM, and Jason Stitt — summed up the significance of these releases as not only a historical document of the music, but of community itself. “We are ecstatic that one of the dates at the Left Bank is being immortalized in this recording,” the duo writes. “Our experiences at the Left Bank Jazz Society performances were also magical because some of our earliest glimpses into the power of this music to create community – and to heal and restore souls – were in this sacred space.”

Though at its core the LBJS was an all-volunteer jazz appreciation society, the organization always had the appearance of a professional business. The 1975 yearbook shows five officer positions, an 11-member board of directors, an 18-member Public Relations Committee, a Prison Liaison Committee (the society had some short-lived chapters that tried to bring the music to detention centers), a Development Committee and an Entertainment Committee. Still, it was ultimately just a gathering of aficionados united by their passion for the music.

“They were just regular folks with regular jobs,” said Fowler. “We had damn-near knockdown, drag-out arguments during the [regular planning] meeting on Wednesday, but on Sunday it all came together.… We didn’t get rich, but we always had enough money to pay the musicians.”

Join the Conversation →