More and more these days, you’ll find bassists at the center of what’s hip and happening in the jazz world. From revolutionary reinterpretations of the genre – like Thundercat’s contributions to Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly and Flying Lotus’ You’re Dead! – to radical reexaminations from within – like Miles Mosley’s work in Kamasi Washington’s West Coast Get Down, or Kris Funn in Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah’s sextet – bass players are helping to catalyze the latest developments in Black American Music.

And all these bassists also blaze bold musical paths of their own as bandleaders. Whether you’re going hard on the dance floor to one of Thundercat’s infectious, nightclub-by-way-of-anime grooves, or swaying to the Pentecostal jazz-rock of Mosley, or absorbing the sumptuous, soulful standards interpreted by Christian McBride, today’s crop of bass greats all owe a debt to the original four-string trailblazer, Stanley Clarke.

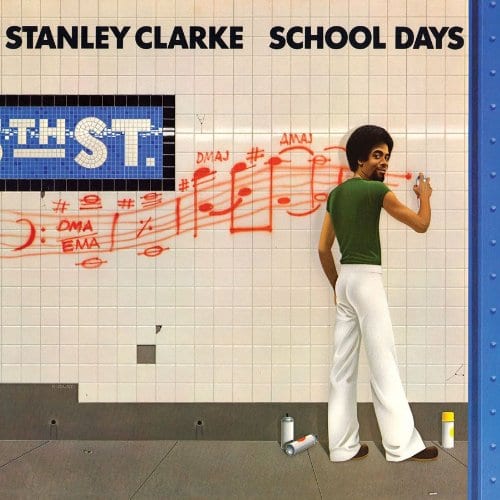

An acoustic and electric bassist of the highest caliber, Clarke helped to pioneer the first wave of jazz-rock fusion while playing alongside Chick Corea in the seminal group Return To Forever. With his own solo debut, 1973’s Children of Forever, and coming into his own on 1976’s classic School Days, Stanley Clarke was the first jazz bassist of the electric age to put the bass out on the forefront. He composed, he led bands, he was often the featured soloist on his recordings. And he helped sever the bass’s singular identity as a supporting anchor, once and for all.

These days, when he isn’t reuniting with his old pals Chick and Al Di Meola, Clarke stays busy in the classroom, touring relentlessly and mentoring the new generation of string-slapping cats. I caught up with him backstage after a master class he’d given during the Smithsonian’s Freedom Sounds Festival—part of the opening weekend celebration for the long-awaited National Museum of African-American History and Culture, where a number of Clarke’s possessions have become part of the permanent collection.

While we certainly talked about his place in the museum, we also discussed the full arc of his career—from the early influence of John Coltrane to his thoughts on reaching the 40th anniversary of School Days this year.

CapitalBop: This whole weekend of celebration really started yesterday with John Coltrane’s 90th birthday. In a podcast you did with your longtime collaborator Chick Corea a couple years ago, you talked about how A Love Supreme was really the “it” moment for you as a young musician. What was it that pulled you in?

Stanley Clarke: I think it was the spirituality connected with that record. You know, when you do instrumental music it can be a little more revealing of an artist: how he feels. If you’re a singer you can hide behind lyrics, and I mentioned this out there [during the day’s masterclass]. I know lots of singers who go out onstage and sing the most joyous, most beautiful things in the world, but they’re really hurting inside. For instrumentalists, we can do that too. But to bring our thing across, you have to dig a little deep. And I noticed when I listened to the Love Supreme album, I said, “This is something. This isn’t just a guy playing like a jazz saxophone player, this is a guy preaching musically. He’s making a statement. He’s proclaiming something spiritual.”

‘Spearheading a movement, you don’t think about it at the time.’

And I didn’t know the specifics, but it wasn’t just a guy playing a jazz saxophone. It was something else. So at a very young age I got very attached to him as an artist, and I went back and got all his records and even a few records after that. And I was that kid in the neighborhood who used to go to the parties with the Coltrane records…. I would just come and put on A Love Supreme and they would have just heard Diana Ross and the Supremes. [Laughs] And they’d say “This guy? Get him out of here!”

CB: I think so much of that record – it’s a spiritual record but it’s also about spiritual freedom, musical freedom, and personal freedom. Do you think, as a 14-year-old, that element of freedom connected with you?

SC: Yeah, it did. You know, because when I studied music, I was fortunate that it sort of became this parallel universe to me: parallel to being the son of Blanche and Marvin, going to school. Even though they knew – you know, I had band classes and all that – but I don’t think they really knew how serious I was and I didn’t know how to articulate that. Because I didn’t feel I needed to articulate that. But I had this other universe.

I think kids have that today with video machines or whatever, all sorts of things, computers especially. But that was my whole world; it was records. And I would listen to things and stay in my room for hours and listen and learn things, solos off of records. And it was just really amazing with Coltrane. I really, really, really—it became like a whole other life for me.

CB: What was it about the life of music? Was it perhaps fate that this is how you came to express yourself?

SC: It could’ve been. But like in your earlier question where you talk about “freedom,” that was the first sense of personal freedom that I had. You know, when you’re a kid your parents are saying, “You gotta go to school.” Even though it was routine and I felt it as a routine, deep down inside I knew there was something maybe a little wrong about this. [Laughs] I should be able to do what I want to do! And through the music I was able to explore, learn at my own pace, and I had something that was mine. It was totally mine. And yeah, it gave me a sense of freedom. I mean, I still have that same feeling.

CB: Is that why you switched from primarily acoustic to electric bass?

SC: Yeah. I mean it was another instrument, the electric bass, and I noticed at a young age that carrying that acoustic bass around, especially to parties, was not fun. Electric bass was cool, I looked better with it, so I had fun with it.

CB: From my perspective, a lot of your career has been about pushing boundaries in jazz and music in general. So I’m curious, is that what attracted you to “fusion” in the early days—that fact that it offered more freedom than strict “jazz”?

SC: You know what’s interesting? It wasn’t a genre that we got attracted to. When me and Chick Corea got together, there were other bands at that time. The Mahavishnu Orchestra was starting. We all kind of started at the same time and we created this music which was, like, jazz, rock, classical, Latin music—it kind of all converged together. At first it was called “jazz-rock music,” and then much later, after we had done three records, they called it “fusion music.” So, you know I was talking to Chick about it: It was really cool to be a part of spearheading a movement, because you don’t think about it at the time.

When you’re a young musician you’re not so calculative that you say, “I’m going to create this new type of music everybody’s gonna love; they’re gonna be into it, all the critics are gonna hate it, but all the young people are gonna be into it and we’ll be famous and make a whole lot of money! Yeah!” No, it doesn’t work like that. You know, Chick was into jazz; he loved Spanish music; he loved classical music. I was a classical bassist, I loved all types of music. And everyone else that was in the band—we didn’t write for radio. No one cared about radio. So we just wrote music that we liked, and it was different than the music that came before us. We weren’t trying to write like Miles Davis or Coltrane, we just wrote our own music. And fortunately a lot of people liked it.

CB: As you stayed in the movement, as fusion got more open, do you think that’s why you liked staying in it, or was there something else about that way of playing and thinking and composing that resonated with you?

SC: Well, Return To Forever, the main band—we had a Latin band, with [drummer] Airto Moreira and [vocalist] Flora [Purim]. And we had all the songs, “Spain” and those sort of songs.

CB: Which kind of spilled over to your first album, Children of Forever.

SC: Exactly. But later, when got into the electric music, we started with [guitarist] Bill Connors and we changed with Al Di Meola and we made four electric albums…. [It all] kind of culminated right at the end with Romantic Warrior. That was a ride: It was like going down a runway. We took off with the Romantic Warrior album, and you don’t leave something like that. Like, every time we did an album we were thinking about the next album. The only time we didn’t do that was after the Romantic Warrior album. I think we got sick and tired of each other and nobody was saying, “God, I can’t wait until the next record! When is that coming?” [Laughs]

CB: I wanted to ask about your involvement with the National Museum of African-American History and Culture. I know they asked for you to donate some items from your life, so I’m curious: How did the museum approach you?

SC: You know, to be quite honest, I wasn’t even sure it was ever going to get done. They said, “Yeah we’re doing this museum for African-American history,” and even called it something different back then. So I thought, “Yeah, okay.” And they said, “You got some instruments, you want to put some stuff in there? We would really like you to be a part of it.” And I said, “Yeah, great!” I had this old bass, I even gave them some clothes, some leather pants. There’s a bunch of stuff back there: an acoustic bass, and I think they’re gonna wait before they expand my display. [Laughs] I have to put a little more work in, maybe I have to go onstage with Metallica or something.

CB: What does that kind of recognition from an institution like the Smithsonian mean at this stage in your career?

SC: You know, it kind of all crystalized in my head a couple of days ago. The bass company that I use – they’re called Alembic, and they’re kind of like the Rolls Royce of bass making. They’re a small group of people that came out of the Grateful Dead. They made a bass for Phil Lesh, John Entwistle, and then me, and Jack Casady. They’re a small hippie company, basically just a bunch of hippies, now a bunch of old hippies. [Looks at Robert Leopold, Deputy Director of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, who’s sitting next to us.] You could be an old hippie! I see something there! So these guys feel so honored that their bass is enshrined in this museum. And so I just didn’t think about it; these guys feel like they’ve made it. Because it’s true, you know hundreds of years from now you’ll see an Alembic bass in there. Whether it’s continued or discontinued, it’s there.

‘Bill Wyman in the Rolling Stones always looked so unhappy, just standing there…. When I started getting into the bass, I used to go, “Well, I’m never going to look like that.”’

But then, as far as my family is concerned, they called me and they said, “Our name, ‘Clarke,’ is enshrined in this museum.” So many relatives came out of the woodwork and they were just blown away; so it’s not just me. I think any display, it may have a name there, but I think there’s a lot of efforts from different people to make that display happen.

CB: I’m picturing your family coming out of the woodwork saying, “So that jazz thing finally paid off, huh Stanley?”

SC: [Laughs] There’s probably some of those! And probably even some, “God! Is he dead?”

CB: Since this is a day of history and reflection, I wanted to pivot to another question about your history. October marks the 40th anniversary of the release of your breakthrough album “School Days.” Does it feel like 40 years?

SC: You know, that song is such a timeless song. And it’s funny: no matter where I am in the world, there’s always some guy in the audience going, “School Days!” There were a couple here today. I’ve even been in the deepest parts of Africa and there’s a guy going, “School Days!” That record was the record for me, that had the widest reach for me as a solo artist.

CB: You talked about evolution during your masterclass just now. Thinking about where you were in School Days, how do you think those compositions have evolved over 40 years, and how do you think you as a musician have evolved in that time?

SC: Well, I mean, sometimes I play those songs where they’re unrecognizable. That’s the benefit of being a jazz musician – or an instrumental musician, or whatever – is that you don’t necessarily have to stick to a form and stick to the way it is on a record. Evolution and development of music, particularly songs, for a musician like myself, is really a must. There’s really no way to avoid it if you’re going to be a real instrumentalist.

CB: We’ve talked about technology a bit. The evolution of technology, the evolution of effects and electronics, the way electric instruments are played and sound: Has that influenced you?

SC: Yeah, absolutely. I would like to say that the one thing it’s done is empowered pretty much everyone to record. You know, back in my day, to make a record, man, wow. When I think about it, I don’t know how we remembered anything. We’d get up in the morning, you’d have to put some clothes on, you had to call the studio, you had to rent some gear, if you didn’t have it you had to hire somebody to take it down, you had to hire an engineer, he’s got to make sure the studio’s right. Then you get there with the idea of the song you had, in your head or written down, and it’s amazing that we remembered anything, man. Nowadays you can literally stay in the bed and start recording, and mix, and do your cover, and everything. That part of it I like.

I don’t necessarily think that technology pushes music education as much as it should. But it does empower people to do things. So you probably have less people that are taking music lessons and studying music today than, say, in my time in the earlier ’70s, late ’60s. But we’ll see where it leads. It’s still young, this thing here, so it’s hard to say what will happen….

CB: It’s interesting that basically 40 years after, the kind of fusion work you did is now the key sound of modern jazz, especially on the West Coast, with the stuff that cats like Robert Glasper and Thundercat are doing. Why do you think it took so long to catch on?

SC: I don’t know, but you know, it’s funny man. Thundercat – Stevie – I met him when he was 14 or 15 because his brother played with me. And I remember him bringing little Stevie to the house and Steve was, like, in the corner, and I’d say, “Come on, man!” He was very shy when he was young. But I am so happy for him. We text each other three times a month: I actually don’t call him Stevie anymore, I call him Thundercat. THUNDER! CAT! And I’m just so happy for him because he’s a real, real, real distinctive, unique bass player. He follows the tradition of, say, guys like me and Jaco [Pastorius] and a few others.

You know, there’s a bass there, but there’s absolutely no reason why you have to stand in the back. You can come out, you can have your own band and do whatever you want. If you sing, if you don’t sing, whatever: You proudly stand there with your Fender, or whatever the hell you have, and he follows that. I really dig what’s going on in the bass world now; it’s not monolithic anymore.

The first bass player I ever saw, and noticed, was Bill Wyman in the Rolling Stones. He always looked so unhappy, just standing there. And later, I found out he was unhappy. [Laughs] When I started getting into the bass, particularly the electric bass, I used to go, “Well, I’m never going to look like that.” I always got the feeling he was a lot smarter than he looked.

But getting back to Thundercat: He’s a smart kid and he’s doing a great thing. I love what he’s doing. I’m happy for him.

CB: What about other younger cats, like Miles Mosley and Christian McBride? Do you dig what they’re doing?

SC: Yeah! I love, love. I’m happy that you mentioned Miles Mosley because maybe he’s getting more notoriety now, but he was so not noticed. He’s really one of the most unusual acoustic bass players. I mean, this guy plays grooves with the bow, and I had never heard that before. And then he has a blue bass! When I met him I said, “What’s up with the blue bass, man? What the hell? This is embarrassing. I can’t even be seen next to you!” He was laughing. But he’s the new thing. He’s got a new record that’s out or that’s coming out and he sent it to me, and I heard it, and it’s really nice. It’s like retro and his voice sounds good, and there’s a nice balance between his voice and bass playing. There’s a beautiful song with just him and the bass—beautiful. I forget the name of it. But he’s a new guy and, you know, the onward march of the bass player keeps going!

CB: I just had one more quick question about Thundercat—or Stevie, as you used to call him. I read in one of his interviews that you once told him, “‘Your job, you’re a servant. Your role is to serve the song.” What did you mean by that?

SC: You know, I find that a lot of artists that I know that are really, really famous – good, famous, whatever – all have this one quality: There’s a certain humility that they have. Even the ones that you think are egomaniacs are not. It’s like, an act—but when you really sit down with the guy, there’s a certain humility, a certain understanding of humanity and the music.

When you do music, there has to be the factor of service because you’re not just playing at people. You’re playing to people, you’re changing their life; it’s a service. And when you have a little bit of that in your head – not too much, but enough – it’s a great thing. And that’s what I meant for Stevie. And it resonated with him, he understood.

CB: I missed you a few days ago at the Howard Theatre, but we’re very lucky to have you twice this week in D.C. We in the Beltway area are also lucky because you usually come through once a year. I even heard you talking about playing the Carter Barron Amphitheater with George Duke. Do you enjoy playing in D.C.? What keeps bringing you back?

SC: I like it, this is where the halls of power are. [Laughs] And my wife loves to come here. She’s from Chile and it’s really fascinating to watch her, like, look at this. You come here or you go to Philadelphia, to downtown Philadelphia, and you look at the beginnings of this country: It’s all there. It’s fascinating for people, they might get a kind of a surface look but they go to these cities and they realize some real, serious people built this country, for better or worse…. I like to watch my wife experience D.C. Every time she comes here she’s just: “Wow.”

CB: And like your hometown of Philly, there’s a lot of great music going on in D.C. that people don’t really know about. So I’m wondering if D.C. cats like Ameen Saleem or Kris Funn, who plays with Christian Scott, are on your radar.

SC: They always were. I remember the drummers. The drummers had a different thing; they played the go-go beat down here and everybody that was from D.C., and into Baltimore, they all have a slightly different way they play rhythm. And that’s a big thing. There are many times I’ve been in California in jam sessions and I say, “Oh yeah, play that D.C. beat.” It’s got a little swing on its backside, and it’s very real.

CB: I wanted to close with this: You’ve been a pioneer, a composer, a soloist, an educator, a husband, a Grammy winner, “bassist of the year” countless times, and now a featured artist in the National Museum of African-American History and Culture. How do you want history to remember Stanley Clarke?

SC: I’m gonna become an astronaut. [Laughs] I’m going to travel to another planet and plant the seeds of bassology. ![]()

Join the Conversation →