‘DC Jazz’ tells a history of the people and places that made D.C. an important home for jazz

Editor’s note: In recognition of Jazz Appreciation Month, CapitalBop is publishing a series of articles throughout April on books that depict the history and culture of D.C. jazz. This is the second piece in that series; you can read the first here, and the third here.

There are dozens, if not hundreds, of books dedicated to the ways in which Duke Ellington, the most prominent son of Washington, D.C., shaped the contours of jazz composition and affected its history. No one can deny Sir Duke’s place in the canon; but where is the place for his teachers, his neighbors, the community that cradled him as a young man in the nation’s capital? What can we know about the place that birthed Ellington and John Phillip Sousa; raised James Reese Europe; provided a home for Jelly Roll Morton, Gil Scott-Heron and Pearl Bailey; and launched Ahmet Ertegun’s revolution in the record industry?

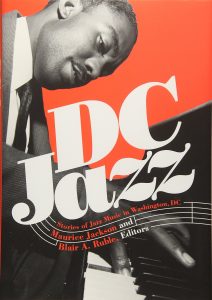

DC Jazz: Stories of Jazz Music in Washington, DC, published in April 2018 by Georgetown University Press, is one of the only — maybe truly the first — volumes to try and capture the role that the District of Columbia has played in shaping the history and style of jazz.

The book grew out of a special issue of Washington History Magazine, co-edited by Professor Maurice Jackson of Georgetown, one of the most celebrated scholars of Black history in the region, and Blair Ruble, a scholar who also authored a book on the history of U Street. DC Jazz collects 10 separately authored chapters, six of which first appeared in Washington History, that discuss the history of jazz in D.C. from Sousa and Europe through the heyday of Ellington and “Black Broadway,” and up to the present. It focuses on the individuals as well as the cultural and political forces in the city that affected the music on a larger scale.

For Jackson, whose scholastic profile includes extensive writing on Black music history and on abolition movements in the Mid-Atlantic, it was crucial that DC Jazz not just discuss the music, a foible he sees in some jazz books. “When one ties [music] to society, then that becomes very important,” Professor Jackson told CapitalBop. “Tie in music to society; tie in the development of music and how it played a role in shaping Washington, but also how musicians were influenced by society.”

During the course of our half-hour chat in his office, which overflows with books, Jackson and I touched on other elements he found crucial in assembling the subjects and stories that went into DC Jazz, as well as broader questions about D.C.’s often-muted place in the jazz history books. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

CapitalBop: Was there any kind of compilation or history of D.C. jazz that, say, didn’t just focus on Ellington, before this book?

Maurice Jackson: I hadn’t seen one. I had seen articles and pieces about different people, like Buck Hill. I was just going through and reading pieces on the great Reuben Brown, who was legendary and used to play at the One Step Down. Whenever musicians came to town, they always wanted Reuben Brown; so he played with everybody, especially at the One Step Down. And there had been books written about James Reese Europe. So, this gave us the chance to address people who want to hear about other subjects and other topics and other periods, because there are so many. I think interest is there now in the city.

CB: Did you see the book as comprehensive, or as just starting a conversation?

MJ: In a way it’s meant to be comprehensive. Its comprehensive notion was not just to talk about the jazz scene itself but to talk about the importance of the jazz scene to society, and link it. I read almost every jazz book that comes out; I just read one on Dexter Gordon and a new one on jazz in Detroit. One thing that I know is, when a person tries to write a book just about the musical lingo, the book’s not very good. But when one ties it to society, then that becomes very important. Tie in music to society; tie in the development of music and how it played a role in shaping Washington, but also how musicians were influenced by society.

Certainly, Duke Ellington was influenced: He was influenced by the Haitian Revolution; he was influenced by Rayford Logan, the great historian at Howard University; he was influenced by Ben Davis, who was a communist leader in Harlem. Even though Ellington gets the reputation of being an arch-conservative, in some ways he was not.

It was a chance for me to talk about Louis Armstrong in Washington, things that people hadn’t talked about. So that was the purpose. Is it a singular book on a singular person or a singular form of jazz? No, it’s not.

There are certain things we hope people write more about. I hope someone writes more about the jazz loft scene that used to be at 7th and F Street. I wish someone would write more about Shirley Horn, her life story, but talk more about music and why it was so difficult for her to make a living in music; the sacrifices she had to make being a Black woman in Washington, D.C.

CB: It’s funny that we have all these institutions in Washington, like the NEA and the Kennedy Center — part of the history is a lot of people doing the DIY thing. CapitalBop does that now with our own thing, or the Ertegun Brothers putting on their own concerts. Was that a theme you saw, that D.C. had to make its own scene?

MJ: Well, two things. Maybe it’s not so much now because some of the young people like Elijah Jamal Balbed and other local musicians are doing quite well, but most of the time anybody, if you wanted to make it, you had to go to New York. Then you came back. So, Duke Ellington did it; Billy Taylor did it; Buck Hill chose to stay in Washington. Nowadays, people like Marc Cary, Ben Williams and others — still people are going.

That’s not true of just Washington; it’s true of anywhere. Ornette and Charlie Haden and Don Cherry all had to go to New York. I think several things are uncommon in D.C.: D.C. is such a stratified city based on race and class, and that really hinders the scene, because many of the upper-class Blacks didn’t see it as their music. You didn’t have that in New York: Upper-class Blacks were jumping at the clubs. So, you had that sense.

Howard University had a music department but it was only towards the ’60s and ’70s when they really started appreciating jazz. Benny Golson, the great Benny Golson, talks about being there and there being no jazz. It’s not so much underground, but it was not necessarily the most popular form among certain people, and then among certain people it was — in venues along U Street and Georgia Avenue.

Of course, D.C. is very segregated. There were clubs in Southeast and H Street that were segregated even though people went in and integrated them, but it was against the law. That’s why the Ertegun brothers, these Turkish guys, played such an important role, because they integrated the jazz scene both at the Turkish Embassy and at 16th and R Streets, at the Jewish Community Center. So, as I say, “Dig this: Two Muslim musicians taking Black music to a Jewish community center.” If we had this type of cooperation today, we’d be in good shape. But we don’t.

Maurice Jackson. Courtesy cpnl.georgetown.edu

CB: Why do you think D.C. gets left out of the wider jazz history? Is it because of the all-dominating narrative of New York or is it because Washington consumes D.C.?

MJ: I think it’s because New York is such a dominating force. That’s No. 1. No. 2, New York just has not just the music scene. For example, you go to a jazz club or concert in New York, you really feel like you’re amongst people that really appreciate music. I go to the Kennedy Center sometimes, and the music is good but I don’t always feel like I’m amongst music lovers; I feel like I’m amongst people who are there to be seen. It’s changing a little bit now. Of course, New York had the clubs and the clubs always existed. In D.C., there are quite a few but they come and go.

CB: To return to the book, you talk about the link between music and society. What voices from the society, the community, did you know you wanted to be in the book?

MJ: Well, I knew, for example, in the chapter I wrote, the introductory chapter, I wanted to touch on the historical nature of the music. James Reese Europe, how he was trained, how he came from Alabama, listening to Sousa as a kid. I wanted to talk about people before Ellington: Will Marion Cook and his influence on people like Duke Ellington to become composers. The racial scene that existed in the period. And, of course, with James Reese Europe, the 100th anniversary of World War I was coming up, so I wanted to talk about his role in that and what influenced that, how he formed a union in the Clef Club.

Then Duke, but I mainly wrote about Duke’s political influences because ideas affected him. I wanted to write about Marian Anderson because so many people bifurcate between different forms of music. But for me, if you’re a real jazz lover you’ve got to love the Negro spirituals, Black classical music, the blues, some country western music — because country western music ain’t nothing but white man’s blues. I wanted to bring all that in through different periods, chronologically.

When Blair Ruble wrote about 7th Street, he wanted to talk about the blues. When we interviewed Bill Brower, there was no one who I knew in the years I’ve been in Washington, who’d been a part of everything. Bill has worked as a stage manager, so he knew all of the musicians — Max Roach and many others like that — so that would be one person to interview about this era. And that would also bring in the jazz loft concerts. After we did this, we realized we’re missing something: We’re missing the Howard element, the UDC element, we’re missing more about women in jazz. And then of course Rusty Hassan; no one knows more about the jazz scene than Rusty Hassan. Started from here at Howard, knows all the musicians, and is just a very nice guy.

It’s a wonderful book and it’s a discussion book. It’s a book that people can sit down and talk about the old days, the new days; and it’s a discussion book that people can use. Mike Fitzgerald writes about the UDC archives and things like that, so if they want to write a thesis or something, they can use the book as a resource.

CB: If you wanted to add more chapters to the book for a later printing, like in 10 or 20 years, what things do you think you’d want to add? Some of that is, of course, unknown to us yet — but what do you think could be added?

MJ: I would add a chapter on the period of the Jazz Loft scene — it was very exciting! I’d certainly have an article on the development of the DC Jazz Festival. I understand there’s a nice underground jazz scene going on. I’ve been to a couple things down by the convention center; a bit about that. Also, something about the young Turks coming out of D.C. now, some of the great young musicians coming out. There are many different angles.

Probably I’d try to get Davey Yarborough to do a piece on the Duke Ellington School. I wanted to get A.B. Spellman to write an article — he was at Howard with Baraka; he wrote a book called Four Lives in the Bebop Business in the ’60s, one of the seminal books in African-American and jazz history. So, there are many, many topics that we could write about.