How Cuneiform Records has remained a label ‘in opposition’ for the past 40 years

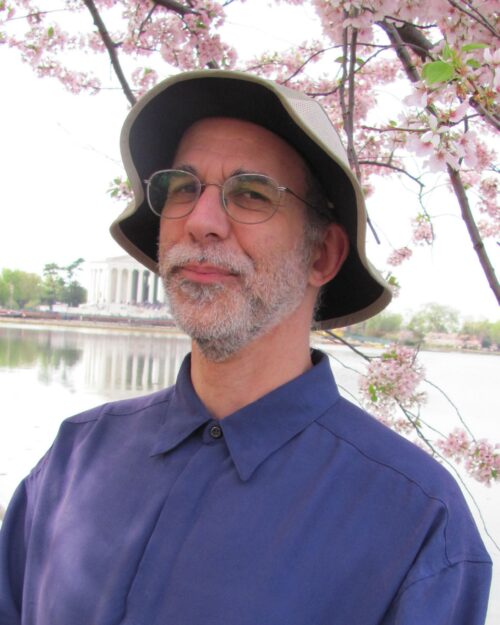

When Steve Feigenbaum started Cuneiform Records in 1984, he had no expectation that it would become his life’s work for 40 years to come. His mission was — and remains — a humble one, he said: to simply make the most interesting record label possible, without going bankrupt.

Well, “interesting” may be an understatement.

Over the course of its four decades in operation, Cuneiform and the mail-order service that Feigenbaum had started four years earlier, Wayside Music, have done much to connect people worldwide with artists on the bleeding edge of avant-garde and experimental music of various strains.

The label has been through its share of lean periods, especially since the advent of streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music, but Feigenbaum remains devoted to recording adventurous, creative music — especially (though not exclusively) by artists in the D.C. area.

“You know, I think that right now we’re in an extremely good, fertile and supportive time,” Feigenbaum said of the D.C. music scene in particular. “And also, a very happy time for Washington-based musicians working in creative music, which has kind of ebbed and flowed over time.”

Cuneiform has been releasing new material monthly throughout its 40th year. That has included a well-received album by D.C.-area cellist Janel Leppin’s Ensemble Volcanic Ash; a collaboration between Leppin and guitarist Anthony Pirog (of the Messthetics); and an LP by fellow District native and cellist Tomeka Reid’s quartet. Cuneiform has also released archival recordings from synth pioneers Mother Mallard and jazz-rock greats the Soft Machine, whose music was an important inclusion in Feigenbaum’s childhood record collection.

Feigenbaum, 66, likes to tell a story from his teenage years to explain the impetus behind the label. When he was 15, he adored the music of modern-classical composer Harry Parch, an avant-garde musician known for creating his own unique instruments. Parch’s music was not very easy to find at Feigenbaum’s local record stores. So, after spotting a new Parch release in the now-defunct Schwann Catalog of recordings, Feigenbaum traveled an hour by bus to place an order for the record at a classical music shop, coming back several days later to retrieve the record.

“Who is crazy enough about music to get on the bus for an hour each way, two times, for a record?” Feigenbaum asked in an interview with CapitalBop.

It was this struggle that made him want to help artists on the fringes reach listeners around the country and across the world. But he wasn’t sure how to do it.

A few years later, Feigenbaum went to England to see Henry Cow, a band at the forefront of the “rock in opposition” movement melding rock, jazz and experimental music. Feigenbaum spent some time with the band and met drummer Chris Cutler, who was just starting a boutique label, Recommended Records.

Cutler’s label, which remains a bastion of experimental music today, inspired Feigenbaum to establish Wayside Music in January 1980. He had been working at a record store part-time, but once the mail-order catalog took off, he threw himself fully into it.

When asked if he does anything for work outside of running Cuneiform and Wayside, Feigenbaum laughed before saying: “Oh hell no, this is what I do!”

He said he toyed with the idea of just opening up a record store, but soon realized that he would struggle to find a sufficient audience for the music he wanted to release in any single location. With the mail-order business, he became connected to a worldwide network of listeners, years before the internet.

“Wayside became a conduit for introducing people to things that they would not find easily in their corner store,” Feigenbaum’s wife, Joyce, who ran the label’s in-house publicity service for many years, told CapitalBop.

In its infancy, Wayside specialized in marketing music from independent experimental labels, but after four years Feigenbaum decided to expand his repertoire and assume a more active role in working with artists to assist them in recording and releasing music. Thus, Cuneiform was born.

Its first proper release was R. Stevie Moore’s What’s The Point???!?! in June 1984. While Moore did not release any more records with Cuneiform, his involvement in the label’s inception made for a fitting cosign, given his legendary status in the lo-fi and outsider music scenes.

At the same time, Moore’s brand of bedroom pop was hardly indicative of the breadth of music for which Cuneiform would become known. Joyce said that the District’s hardcore music scene shared a lot of spiritual similarities with Cuneiform’s aggressively genre-bending offerings. Punk, after all, is more of an attitude than a type of music.

Feigenbaum said the District music scene and surrounding media paid scant attention to the label’s work until recently. But that never stopped him from showcasing local artists and attending performances constantly at venues like Rhizome DC, which is just down the street from his home in Silver Spring. (Feigenbaum was a regular presence in the audience at CapitalBop’s DC Jazz Lofts during the 2010s, too.)

The label’s artists typically stop at venues like Rhizome when they are in town, as local artists by no means make up the bulk of the label’s roster, which spans across cultures and continents. In fact, half of the records issued by Cuneiform this year were recorded by European groups, including the Soft Machine, which has released music on the label for years.

In the past decade-plus, Cuneiform has adjusted to the realities of selling music online. Feigenbaum said the interent had allowed him to expand Cuneiform’s audience. Nowadays, Cuneiform does much of its business through the online marketplace Bandcamp.

“Bandcamp is: A, amazing, and B, the only reason why Cuneiform Records still exists,” he said. On principle, the label does not feature its music on any other streaming platforms. Feigenbaum tried putting Cuneiform’s catalog on Spotify for a short while. “It was awful, and there was no money in it, and it was ridiculous,” he said.

“For many years, running a label was kind of a viable thing. You know, back when people actually bought music,” he said. “And I had a crisis about seven years ago.” With the music business somewhere between realignment and collapse, in 2018 Feigenbaum was forced to all but shutter Cuneiform and Wayside and lay off his small staff. But in subsequent years, he was able to restart the label on his own.

Today, the whole operation consists of two full-time staff members and two part-timers, with most of the efforts being poured into the mail-order side of the business. Feigenbaum said that Cuneiform is really just him and Joyce, who works part-time.

For better or worse, he thinks that the downsized business model allows him to do what he wants in a more unfettered way than before. At its core, the label continues to do the same thing it’s always done: spit in the face of musical conventions and the industry behind them, acting as a haven for artists trying to do the same thing.

Cuneiform Records, DC, DC jazz, Henry Cow, Janel Leppin, jazz, R. Stevie Moore, Soft Machine, Steve Feigenbaum, Tomeka Reid, Washington