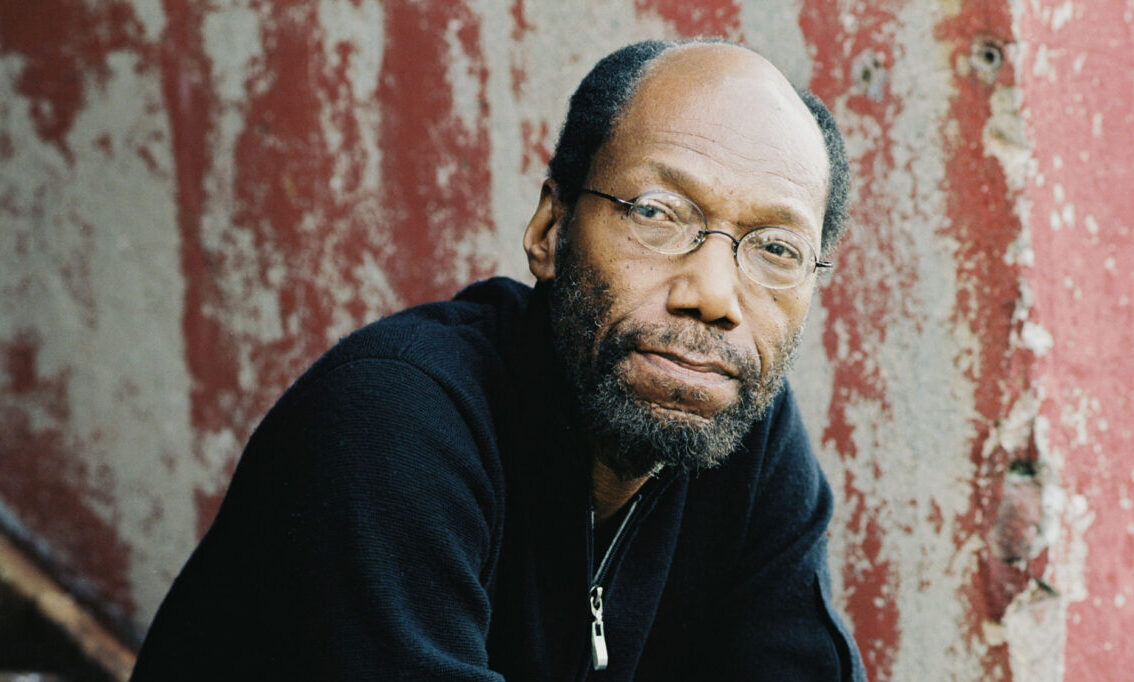

Trumpeter Charles Tolliver is known for many things: co-founding the highly influential Strata-East label with his collaborator, the pianist Stanley Cowell; co-leading the ferocious post-bop group Music Inc., also with Cowell; and contributing as a sideman on many now-iconic records from the mid-1960s and beyond. What fewer fans might remember is that he attended Howard University from 1960 to 1964, as a pharmacology student, and shared a dorm, marching band and nights out on the D.C. jazz scene with Andrew White, a beloved D.C. saxophonist and jazz legend.

Tolliver, now 81, was born in Jacksonville, Fla., where he lived with his family until he was five, when in 1947 they moved to New York City. The music bug bit Tolliver shortly thereafter, and after inhaling the Norman Ganz-produced 78s lying around his family apartment, he spotted a cornet in a pawn shop window. A part-time job at a Harlem apothecary led him to Howard’s pharmacology school. He arrived in Washington, D.C. at a time when the jazz scene was at a peak, especially along the U Street Corridor, with a resurgent Bohemian Caverns.

Meanwhile Tolliver was developing a deep affinity for John Coltrane, an influence that can be heard throughout Tolliver’s six-decade career. Take 1972’s “Drought,” or 2019’s “Hit the Spot,” for example. Both are Tolliver compositions and performances that echo the unrelenting kinetic group motion, ritual evocations and towering piano harmonies typical of Coltrane’s later work.

In the late 1990s, Tolliver delved more deeply into Coltrane’s sound when Trane’s longtime bassist Reggie Workman approached Tolliver with a proposal to arrange the legendary Africa/Brass album with a new choral section. Tolliver’s arrangement of the Coltrane masterpiece has been periodically performed over the years – one notable show had Archie Shepp and McCoy Tyner onstage alongside Tolliver’s big band at the Blue Note in New York in 2012 – but not since its 1998 debut has the work been performed with a full choir.

So it is particularly significant that Tolliver is not only bringing his Africa/Brass arrangement to the Kennedy Center this Saturday, Oct. 21, but will also be joined by the iconic vocal group based at his alma mater, Afro Blue, who will sing the choral parts.

CapitalBop spoke with Tolliver over Zoom last Thursday from his home in New York, hearing stories of his early years in the D.C. jazz scene’s golden age, his love for Africa/Brass and the legacy of Strata-East.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

CapitalBop: Can you talk about when you were a student at Howard? What were your impressions of the D.C. jazz scene then? How did you interact with it?

Charles Tolliver: Even though I was majoring in pharmacy, a lot of my time was spent in the brand-new fine arts building. They were doing a lot of construction in those years. They had just built the new Drew Hall … that was my dormitory. My first impressions of Howard were, well, I was excited to be in college. That was quite a freshman class: On my dormitory floor was Andrew White, Harold Wheeler – who went on to do a lot of Broadway shows after he graduated – Stokely Carmichael, Donny Hathaway. There were a lot of people who were going to make an impression later on.

CB: Did you play with Andrew or go out and play with him?

CT: Well, it just so happened that in those years the marching band for Howard’s football games was the ROTC band. So, if you wanted to play in there, that’s what you did as a musician. … There was a little cabin at the southern end of the field and there you would go to audition. When I went in, everyone was gathered around a musician who was wailing away on his saxophone, and it happened to be Andrew White [laughs]. That’s how I met him. We would play for half-time for Howard’s football games at home.

The jazz scene was actually quite going on at the time. There was the famous D.C. tenor sax player Buck Hill, who held forth at a place on Georgia Avenue near the old baseball park – Griffith Stadium. I forget the name of the club, but he would be playing in there, and of course we’d go in there and listen to him. And the Bohemian Caverns had just started up with Tony Taylor and his partner; Andrew went in and co-opted the place with his JFK Quintet. I believe that for his whole four years, that’s where he was on the nights the club was open. I don’t know if it was open the whole week when it started, but certainly as the years moved on it became a weekly gig for Andrew.

During that period, I met Billy Hart – who was born and raised – and a lot of the other local musicians: Maurice Robinson and Charlie Hampton, two alto players; Butch Warren; there was a well-known alto saxophone player named Hirschel McGinnis who had a style like Eric Dolphy, he was terrific; Marion Brown was living there at the time. So, that first year was getting to know all those musicians. Joe Chambers came into town in that first year as well, and never left. He became the drummer with Andrew’s JFK. Matter of fact, around my junior year, Joe and I were living in the house of Walter Booker – because Walter Booker was the bass player in the JFK.

That pretty much is the short of a very long story during my stay there in D.C.

CB: What impact did those musicians have on you in your budding musical identity?

CT: Andrew White was stratospheric because of his born gifts. He was like a Mozart, born with everything. The two alto players, Maurice Robinson and Charlie Hampton, I hung as much as I could with them. They had mastered bebop. Charlie Hampton had a weekly gig at one of those circles they have in downtown D.C. – I forget which one now – but there was a well-known club right there on the circle. Steve Novosel was the other musician I became very close to while I was there, and it was just Steve and Charlie Hampton playing in that place. Every chance I got, I would go there to hear them. Those two absolutely made a big impression on me because I was trying to figure it all out. I was still a teenager!

CB: Did you meet Brother Ahh (then known as Robert Northern) during that time? Was that the beginning of your relationship with him, or how did that relationship — which led to his albums on Strata-East — come about?

CT: When Stanley [Cowell] and I started to roll with Strata-East Records, Brother Ahh was one of the musicians who came in and wanted to put something together with us. That was when I got to know him. We would only see each other in passing, at one of the clubs or something like that. We did it: We put his recording out, and interacted [for] two years or so. Then I didn’t see him again for the next 40 years. The next I was to see him was at the revival of Thelonious Monk’s famous Town Hall concert. The 50th anniversary was celebrated at Town Hall. … He was probably the only surviving musician in the audience that night.

CB: He was also on Africa/Brass, which is the reason we’re talking today. Could you talk about the origin of this project?

CT: There wouldn’t be an Africa/Brass project without Reggie Workman. In 1998, because he knew I was messing around with big-band stuff, he said that he wanted to do something with it and he wanted to use a choir. He had tried to get the scores, but in talking to McCoy [Tyner], nobody knew where everything was. I think he said something to the effect that Eric Dolphy’s charts that he had done had been destroyed. In any case, I said “OK” and I set about transcribing it, exactly as it is on the recording, and then putting the choir to it afterwards. I think the premiere of it was at Damrosch Park with a choir.

It was put away for the next 10 years or so, and then Reggie did it at Lincoln Center in 2011. … I think Impulse! decided they wanted to do something and I did it with Archie Shepp as the John Coltrane soloist and with McCoy at the Blue Note — all of this centering around the 50th anniversary. I did it a couple of more times, but not with a choir. The only time it was done with a choir was the original premiere with Reggie. I’ve decided to do it with Howard University’s Afro-Blue and that’s how it got to the Kennedy Center.

CB: What is significant for you about returning to this piece?

CT: Well, for me, John Coltrane was everything as a kid, and still is. He exhausted everything [laughs]. He exhausted us. It was like John Lewis: “Get into some good trouble.” He was getting in good trouble all the time. It’s just magnificent. Africa/Brass was one of his iconic works. The choir gives it another whole dynamic, so it gives me an opportunity to play this work of his with that added to it without detracting from the original intent. … It’s always a joy for me to delve into Trane with the Africa/Brass because they’re basically just wailing away on all of those horns.

CB: What inspiration did you draw on to score the choir? Maybe I’m overreaching with the Howard connection, but is it anything like what Donald Byrd did with his choral projects, like A New Perspective?

CT: Not at all. I stuck to McCoy Tyner’s voicings. You’ll hear it at the concert. It requires, to really pull it off with a choir, somewhat of a trained group of singers. They need to be on pitch, if you understand what I mean, but at the same time enjoy it as if they were in church. Singing it like the choirs of the great churches.

CB: We’ve alluded to your long work with Strata-East, but I wanted to you about it directly here at the end. With the resurgence of vinyl and especially the culture of reissuing classic albums like the Strata-East catalog, where do you see the label’s legacy in music today?

CT: Strata-East was maintained to be a monument to both my beloved partner Stanley Cowell and Clifford Jordan: They were visionaries, too. I’ve kept it going because of the love and devotion that they gave when we first started. … Basically, Strata-East should be a model to the younger generation today if they delve into the story of it. What we did was not new, in terms of musicians or people starting a record operation with one record or two records. What was significant about us is that we built a serious catalog that stood the test of time and did not go away.

From time to time, I would hear, “Strata-East had become defunct,” or “didn’t exist anymore.” It never became defunct and it always existed. I think that what we did, didn’t go past someone like Prince. Prince was paying attention, which is why he started to do what he did. I think that musicians, if they want to, can do their own Strata-East. Because, basically, it’s about ownership: There’s a heck of a lot of difference between owning a master as opposed to, on paper, supposedly being compensated for royalties off of a product. There’s nothing wrong with that as long as you understand the dynamics of your employment as a musician for hire. Both things work; in my case, I decided that I would stick with that modus operandi, and here we are.

Join the Conversation →