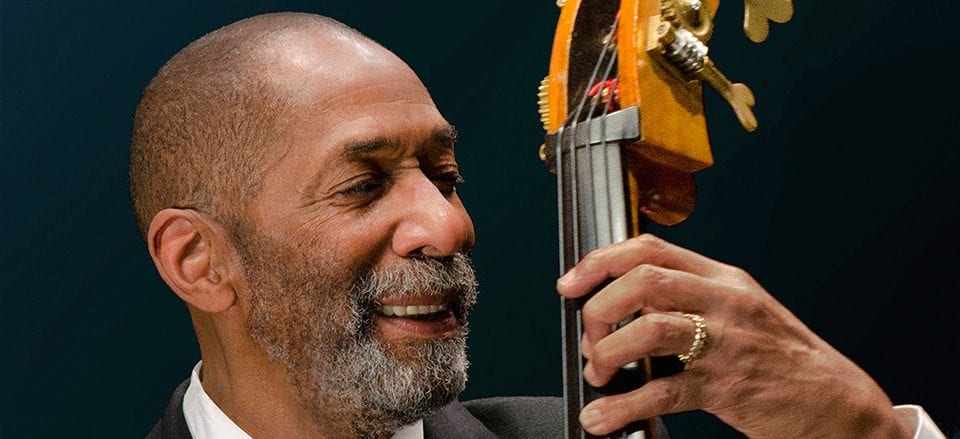

Ron Carter performs all three nights this weekend at Bohemian Caverns with his Golden Striker Trio. Tickets are available here.

Miles Davis is still the forefather of our modern cool, and his 1960s recordings have a lot to do with it. In that rambunctious decade, Davis took the contrarian grin that jazz had always cast at society, and pulled it back a few degrees: Devil may care, devil may arrive in his sports car a few hours late for the gig, devil may ignore his audience altogether.

But the fascinating thing is how much strain, heat and devotion comes through in his music from this era, most of it made with the so-called Second Great Quintet. That group settled on a new formula, something approximating both anguish and indifference. Gestures were small, bravado was absent.

Why do I revisit this now? Because, unsurprisingly, the best example of that quality was also the easiest one to miss. It was Ron Carter, the quintet’s bassist. Like Davis, he committed himself to elegance, but buried a rough kernel of disdain and critique inside. He used a powerful mastery of technique to bring long-toned, liquid sound out of the instrument, eliminating sharp edges. Throughout his career, Carter has returned time and again to the Miles Davis composition “All Blues,” even naming a solo album for it—I presume he appreciates the way that the song both accommodates and resists the form of blues, the way it rises and releases. “All Blues” sounds like a deep breath in a time of duress, an attempt at letting go.

Ron Carter’s one of those musicians who seems to have effortless control over his instrument, but he doesn’t give you that giddy vicarious feeling of a virtuoso at play (for that, think Christian McBride, or even Thundercat). Beauty is work, and it’s defiance.

Carter began his musical life playing the cello, and went on to study classical bass before earning his stripes in the late 1950s and early ’60s with Chico Hamilton and Eric Dolphy. He’ll be best remembered for his work with the Second Great Quintet, but in the 45 years since that band split up, he’s done his best to make us forget it: He’s one of the most prolific sidemen in the history of jazz, and his own projects run all over the map, from funk-dealing fusion records like Uptown Conversation to a handful of stately duet recordings with Jim Hall, Cedar Walton and other greats to overlooked efforts like Parade, a gem featuring almost exclusively Carter compositions, rendered with semi-large-ensemble.

The NEA Jazz Master’s live work in the past few years has mostly centered on his Golden Striker Trio, a drums-free band that plays originals and jazz standards with textbook proficiency. The legendary pianist Mulgrew Miller was a member until his death last year, and although his shadow is long, the band soldiers on, now with Donald Vega in the piano chair. (Russell Malone plays guitar.) That group will be at Bohemian Caverns this weekend for a three-night run. In anticipation of the performance, Carter spoke to me via phone from his Manhattan apartment.

CapitalBop: You began your musical life as a cellist, before moving to bass — partly because of discrimination in the classical world, I understand. I think the beautiful thing about your bass playing is your equanimity, your command of sustain, and your precision. These seem like things that might have something to do with the cello.

Ron Carter: The cello is one-quarter the size, the strings are one-fifth in diameter. The instruments are so different, if there’s a carryover it was learning how to practice and make my lessons matter…. The instrument itself opened up my musicality and possibilities of practice that I may not have known were there.

Unfortunately, I’m so busy with the bass, I don’t have the time to really play the cello anymore. Only occasionally, for my own delight, or the amazement of my friends.

CB: Not only are you one of the most widely recorded bassists in the history of the music, your own solo output has varied widely in terms of style. What has remained a constant for you?

RC: I’ve always tried to find the best notes to make the music have a life of its own. When I’m playing with other people I’m in an accompanist’s status. I like to think of my bass lines, that if you could take everything else off it would be a song in itself. I tell my students: I’ve got to hear the form, the shape of the tune, how you’re playing alt changes, the rhythm. That’s part of the process of making me a part of their music.

What I’ve always tried to do is make the music I play with the various groups sound like I am supposed to be there. The way to do that is to understand as quickly as possible what they define their music as being. And how do I fit into the slot that they’ve defined in their music?

CB: A bassist is often seen as a ballast for a whole band; even though you “walk” your bass lines, it can feel like the whole band walks all over the bassist. But with you, you’ve always seemed to deliberately develop really meaningful one-on-one relationships. You seem to be a big fan of duets, whether with other bassists like George Duvivier and Buster Williams, or pianists like Cedar Walton, or guitarists like Jim Hall. What do you value about the format, and what has it taught you about ensemble work?

RC: I don’t have a preference—it just happened…. Duos are not my preferred format. I always just go with the format that best offers me the chance to learn more music. But the smaller the format, the more you don’t have to play as loudly or as hard, and you have fewer people’s worries to consider. I just have to make the music sound like I belong.

Each duo has its own idiosyncratic motions. Me and Houston Person, or me and Russell Malone, or me and John Lewis…. I’ve done duos for a very long time. There was a club in New York called Knickerbocker’s that only had duos. It isn’t so much the size of the group as it is what the people can bring to the group. In this case just two people have to handle it on their own.

CB: You will be playing in D.C. with your Golden Striker Trio. What do you like about the somewhat uncommon format of that band: bass-guitar-piano?

RC: It’s intimate, I have fewer people to contend with their point of view. There’s no drummer who could overpower you, especially on the softer tunes. Volume is never a concern…. It’s a nice texture, and it allows each texture within the bass, as different as they can be, to come out and be itself on every song. But because we have three people, the arrangements change every night depending on the combined decisions of all the members.

CB: You were with Miles Davis for perhaps his absolute most influential years. What is the biggest lesson you gleaned from him?

RC: Every night you play, it’s a chance to play some great music — don’t miss that opportunity.

CB: In Notes and Tones you talk about musicians — particularly bassists — overvaluing strength and volume, rather than sensitivity and stamina. Do you think this is an issue today? What do you tell young musicians to help them break out of that mentality?

RC: I think it’s the same today. About 15 years ago the notion went around that if you play without a pickup, without an amp, playing natural, you’re fabulous. I’ve been against that concept. I think those players who play like that—I have all the respect for them—but it kind of sacrifices a lot of the opportunities, with regards to texture and tone.

CB: You recorded with Gil Scott-Heron on his breakout album, Pieces of a Man, which means you recorded the iconic bass line to “The Revolution Will not Be Televised.” He was an important figure in the music and in American thought, and he has a special place in the hearts of residents of D.C., since he lived and worked here for many years. What struck you about the young Gil Scott-Heron?

RC: My only relationship with him was in the studio. He seemed like a very sensitive young man who had a real view of the world through his poetry. He had a poetry that was in the style of LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka, and Jayne Cortez—the spirit of the ’60s. I thought for someone with that point of view to do it with jazz behind him was perfect. And I wondered if other people would pick up on it. I think he really led a lot of those sorts of artists to put jazz together with their poetry.

I did a record with Jayne Cortez where she had a band behind it, and that worked beautifully. And I think Gil Scott-Heron was a father of that. Now he’s looked at as a forefather of hip-hop and all that, too.

CB: When you did your album Dear Miles, some pieces made direct references to the original recordings, like “Bye Bye Blackbird,” and others didn’t. How did you decide which to treat in that way?

RC: A lot of those tunes I’d been playing even before I played them with Miles. But that record was a reflection of my feelings of him, and what it was to play with him. I delayed doing that record for a long time because everyone was doing that kind of record [Davis tributes]. I wanted it to relate to Miles and my point of view of him. It took a while to get this concept to sound okay to me: I think if he were alive today, he’d wonder how I got the sound and why I made the choices I did. He’d say, “Hey man, why’d you do this and that?” And I’d be happy to explain it to him.

CB: You tend to make it a point to play at Bohemian Caverns when you come to D.C. Not every musician of your stature plays at that club; it’s not a huge room, and there are bigger venues in the area that you could fill. Why do you like playing there?

RC: It’s a nice room; it’s got a nice sound in the room. And it seems to me that people of my stature — however you’ve defined it — have a responsibility to play at these clubs and see them rise to the level where they ought to be. The people who come out tend to appreciate the music, the management appreciates the music, and it’s just a very good place to play. It disappoints me when other musicians don’t want to support it too.

[…] Caverns, the bass eminence Ron Carter holds down a three-night residency this weekend; check out our interview with him, and hurry to get your tickets if you want a place in line. The local pianist and composer […]