Anthony Braxton on his six decades in music: ‘It’s about the hope of the future’

Life is an experience, a human experience, that can, as it mounts over time, bewilder even the “friendly experiencer.”

Twenty-seven years ago, I met Anthony Braxton during an elevator ride at the Library of Congress. I had waited too long to secure a ticket through normal channels, so my friend, the late Larry Appelbaum, had found a way for me to attend the saxophonist’s premier of “Composition No. 222.” But Larry’s “tickets” required me to access Coolidge Auditorium through a stage entrance. I said nothing during those few minutes of vertical transit with one of jazz’s most prolific, fêted and singularly obscure artists as he made pleasant, erudite conversation with Larry and whoever else was there with us in the confines of that small swatch of time and space.

I might have been truly bewildered if I had known of the strong symmetries that would bind that brief, silent meeting to a rich conversation more than a quarter-century later. Mr. Braxton and I engaged earlier this week via Zoom as he prepared for a return to D.C. this Saturday, March 8, when he will present new works and reprise “No. 222,” again at the Library of Congress. This weekend the artist will also be celebrating the library’s recent acquisition of his collected papers.

Braxton was awarded a MacArthur “genius” grant in 1994, and is the deserving recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Doris Duke Performing Artist Award and a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters fellowship. Through his long membership in the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), the better part of three decades spent in academia, and his prolific, often dense writing, Anthony Braxton has made a penetrating impact on several generations of jazz and other musicians.

Strong symmetries? The show that I heard in 1998 was also on the eighth of March, and you will read how mention of a different elevator ride at the LOC found its way into our conversation. We talked about Sun Ra, who frequently extolled the cosmic significations of the number 2. Braxton’s theoretical superstructure is anchored around the number 3. “Composition No. 222” — do you see it? The saddest symmetry comes in the form of an acknowledged absence: Last week as I was working to schedule this interview, I learned of the passing of Transparent Productions founder and our dear brother, Larry Appelbaum, whose supportive presence surrounds this amazing conversation. Thank you.

CapitalBop: My doctoral research interrogated Butch Morris’s Conduction system. I’ve also written a monograph that explores Sun Ra’s thought. All three of you worked from clearly defined systems — Butch’s system of Conduction, Sun Ra’s heliocentric approach. In interesting and very different ways, you were all trying to negotiate the tension between freedom and structure. If I can paraphrase something you said to Graham Lock: Our understanding of freedom currently does not teach us enough about responsibility. When we are really honest about it, I wonder if any sensible notion of freedom must look like an intensified sense of responsibility.

Anthony Braxton: I can relate to what you’re saying. I would go even further. I think since the middle of the 1960s moving into the 70s, certainly there was a complexity where political men and women, African Americans in this case, would begin to push this way of thinking that improvisation is more important than composition, is more important than symbolic languages. And more and more, the African-American community, especially the artists, would come to a point of stall. That is to say, it would stop evolving. And to this day, in my opinion, the African-American community, especially the artists, have stalled, and as the result of stalling, suddenly this idea of “improvisation is more important than anything else” would emerge. But I have never agreed with this idea. In fact, I wouldn’t say I’m against it, but I would say, when applied to my own work, this idea of runaway improvisation was never what I was interested in. I was interested in being the best student of music that I could be. And how can you be the best [if] you reject notation? After all, notation is just a record of how you built something — the foundation of how you built something; the foundation that can help you discover the meta-reality of creative music.

CB: You know, Sun Ra did not embrace the term freedom; he associated freedom with death. Butch used to tell me that free improvisation was beautiful, but once you do it, it’s gone, and wouldn’t it be lovely if you could resurrect those good ideas when they happen and repurpose them in new contexts? I actually see a lot of similarities between the way you handle the ideas of mutable and fixed variables, and the way that he used his Conduction vocabulary to give people something like brackets that could be filled with their individual contribution. How do you see your work in comparison to the way that Butch was handling it from the bandstand with the conductor’s baton?

AB: Well, I approached the great discipline of music based on my heroes. Whether it’s Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers or Bill Haley and the Comets or Dave Brubeck quartet with Paul Desmond, and later the great Arnold Schoenberg, Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage. The experience I had with learning about their music and taking it in would help me to understand that, No. 1, I’m not a jazz musician, and I’m not a classical musician. I’m a professional student who has spent his whole lifetime trying to evolve. … Because even in the early period it was clear to me that we were — in that time period, anyway — moving into the 21st century. And it’s not going to be enough to just play the repertoire of our heroes … but rather this is an opportunity to make things fresh again, and to find the tools that can push sonic constructions in a way that is flexible and can be applied to many different areas of the music. For instance, I remember maybe five to 10 years before Butch’s system, I had established my system with the ground floor being: language music. And by the term language music, I was talking of sonic geometrics, sonic geometrics on the 12th plane. Continuous state. Polarity logics….

I try to also create foundational options for the friendly experiencer to embrace some of these materials starting from, you know, foundational logics, foundational advancements or extensions into spiritual platforms. The Tri-Axium Writings [Braxton’s three-book series, written from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, exploring the nature of creative music] would be the first set of writings that would seek to talk of a specific logic, to talk of transmutation of that system and for the third-degree questions and answers. I would use that model because number 3 is the number of my system. I try to design it in a way where the friendly experiencer might be able to take in what I’m talking about or writing about, but in the end, it’s not about me. It’s about the friendly experiencer who is looking for something. And part of that something, I felt, was the spiritual components of what was evolving.

‘What we call jazz is a sonic continuum. It’s not just about celebration of the past; it’s about the hope of the future.’

Sixty years later, I’m at a different place than in the original beginning phase of my work. But in the end, some kind of spiritual logic is needed more than ever, especially for our young people, because they’ve grown up with no attendance at any kind of church. Mom and Dad was not there. 90 percent of the marriages, including my marriage, would break up. And so, you have two or three generations of young people who have no understanding of what spirituality is. They’re thinking spirituality is when you go to the church and when you read the Bible. In fact, every group, long before the solidification of Western art [and] Western cultural discovery, were working in that same avenue of African-American spiritualists — the Egyptian spiritualists who built the whole structure of the concept of spirituality and the formulations of spirituality, and what sort of systems could be built to help people, as opposed to what has happened to Christianity — which, by the way, as you know, started in Africa. Christianity did not start in Europe; it was borrowed – quote, unquote — from the work of the Ethiopians. The whole structure. Ptolemy was a part of that transfer. But in the end, every ethnic group has its own way of looking at spirituality, and in looking at it in their own way, we see a composite aesthetic that is universal.

Yes. So, more and more, I will come to think of myself as a student trying to learn about spirituality. But I’m not trying to get there. I’m interested in moving closer to the target, but I’m not interested in arriving at the target.

CB: You and Sun Ra both place tremendous emphasis on intuition as a necessary part of creating music or doing anything that is genuinely creative. And I’m wondering, how does that emphasis on intuition translate through your system, which could be seen as a series of codes? That might not be a natural fit for some people to understand — the fit between intuition and this language-vocabulary for music that you’ve developed.

AB: Very good question. When I joined the Association for the Advancement of Creative Music, the AACM, I will never forget that Lester Bowie was the first in our group to say that the last thing you need is precision, especially when you’re improvising. If you’re playing what you know, that’s a very different idea of jazz, because the original model was to play what you don’t know. Lester would then talk about Winton Marsalis, and I won’t go into that. They were not positive to one another. But listening to Lester Bowie would help me to grow in many different ways. Later, I would teach my students that the goal is not to make it perfect. The goal is to do the best you can do. And if the subject is improvisation, and we’re talking about music improvisation, the last thing we need is to play what you already know, because that’s not what the science of evolution is, especially for African Americans. You had to leave some space to make a mistake, and if you haven’t made a mistake that means you’re playing what you know.

And if you’re playing what you know, then we go back to the codification of the Europeans and the development of the notation that came out of that, which I bow to out of total love and respect. But the Chinese had notation. The Egyptians had notation. So even the concept of notation would have a space where it goes outside of the concrete — and that has, in my opinion, been one of the factors that would make jazz music so important. Meanwhile, by 1955, the African-American community would basically walk away from jazz. Motown had come into play. As you know, the African Americans and Africans love to dance because to dance is to work with the vibrations of sonic continuum or continuous silence and imbalances. By 1955, African-American adults really turned their back on jazz. As if the only thing that mattered was something that was beautiful and that you can dance to.

I come from a tradition of men and women who loved to dance, but that wasn’t what their music was about. It was about building knowledges, different knowledge components that could be used in many different ways. And that movement was foundational. By the 1960s and ’70s, we would see complexities all over the place with musicians my age, who never learned to read notated music, musicians who had no interest in any kind of notation, but they were playing something that was very valuable. I think of Albert Ayler. Albert Ayler might not have been a super virtuoso, but his music was a virtuoso music that opened up another door into the world of sound, on the plane of sound. It was because of Albert Ayler and Charlie Mingus and Sun Ra that I would go to language musics that could be drawn out.

CB: I want to ask you a question that has to do with notation. So, at around the same time that I met you at the Coolidge theater, I had an oppo rtunity given to me by a beautiful sprite named Trudy Morse [editor’s note: Morse was a beat poet and self-appointed “Jewish grandmother” to several jazz giants, including Braxton and Sun Ra]. Bet you remember Trudy.

AB: I most certainly remember Trudy.

CB: Trudy got me an interview with the great Cecil Taylor. So, I’m in the elevator with Cecil, and he’s kind of boasting about the deal that he has cut with whoever writes the checks at the Library of Congress: He’s getting one large sum of money to do the performance, and he’s also getting a separate fee for the score. So, Cecil’s in the elevator, and saying something to the effect of, “Wait until you see what these white folks are going to get for a score!

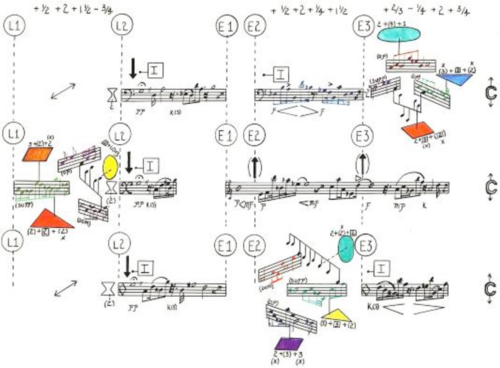

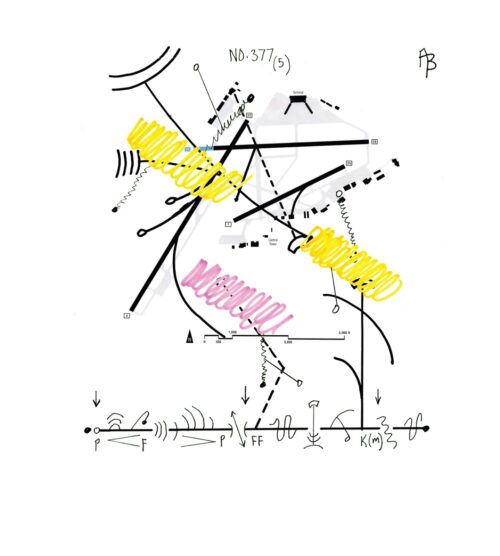

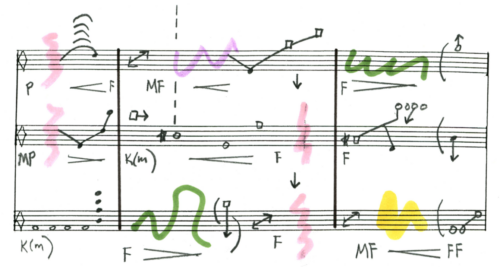

You are famous for using these graphical scores that to more conventional musicians and also to more conventional listeners seemed obscure, perhaps affected. And I wonder if you can — I wouldn’t dare ask you to justify the graphical scores — but explain to us why they were such a valuable part of your production and your methodology at that time in your life.

AB: I wanted to have an image logic that I could go to and celebrate a particular sonic geometric shape. Rather than have a system of chromatics, which was part of the 20th century, I wanted to have a tricentric model that would allow for visual shapes, one and two, stable logics starting with traditional notation and evolving into color spectrum — into language, from humor to march[ing band] music or whatever. And finally — on the third plane — that could give me a tool that can help me to better understand which way I’m going.

The problem with non-notation or symbolic imagery is that you can’t always go back to it because it’s impossible to remember all of that if certain parts of it are not written down. I love Cecil Taylor. I was beat up by Cecil Taylor’s enemies in grammar school and high school. I always loved Cecil, but I did not feel that his way was the way for me. I respected his great music but I wanted a music that I could go back and trace to the foundational components, so that it will keep me on the same track, and that would be one of the differences. Where the sonic geometric labels would give the friendly experiencer an opportunity to say: Oh, it goes like da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da — staccato logics. Bee-boo-bee-boo – intervallic logics. [Braxton makes a honking sound in the back of his throat] — sound mass logics. Bop, bop, bop — single note logics. All the way up to 12 [the total number of music logics in his system].

And with that, suddenly, I can bake a cake. I can bring Language 1 with Language 4, define what the relationship’s going to be like and then add and explore extra language, and then I could have something to work with here. And not only that, I could go back to it and remember how I got there and, in some cases, do it over again and use the same components, but make a different composition. This is why in the early period, I started the solo musics. Just the saxophone by itself, playing the sonic geometrics in one form or another, would help me better understand syntax and the evolution of syntax.

That’s how everything started for me, because I wanted to get away from my heroes: Paul Desmond, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Alber Ayler, Lester Young — the good man that no one talks about anymore — Coleman Hawkins. All of those guys were original and totally dedicated to the music.

‘Creative music more than any music tries to make an experience, the kind of experience that can help a person in the inside and on the outside.’

CB: There’s a very nice documentary on Sly Stone, produced by Questlove, that’s out now. Sly Stone might be an easily accessible example of someone working within popular music who achieved through their work something comparable to what you call being a trans-idiomatic artist. I’m wondering if you would agree with that assessment, and if you are willing to go out on a limb to identify within contemporary popular music — the music of young people, the music of dance clubs — anyone that is even approaching the idea of being trans-idiomatic.

AB: Very wonderful question. I’ll go back to the ’60s. You remember the group Earth, Wind and Fire?

TS: Absolutely, Phil Cohran’s project.

AB: Phil Cohran’s project — that was a restructural ensemble that was not just thinking in terms of making money or getting a hit, but using the great discipline of music based on composite reality and composite world musics.

Earth, Wind and Fire was one of my favorite groups. And every now and then we would meet, because they’re from Chicago, and so we would meet up in different parts of the planet and have to laugh because there was more support in Europe than in America. That has always been the case. As for other musicians, there were at least maybe five to 10 so-called popular artists who were much more than what the critics gave them. They pushed them in the popular domain, but in fact there were many groups that were pushing forward — not just trying to make money, but to push the music forward, which pushed their humanity forward, which pushed their invention forward. Incredible people.

There have been more innovators in the popular world than has been credited. Most of the groups have been kind of reduced to if they were able to make a lot of money or get something that sold and they made a million dollars. I’ll tell you who I like: Michael Jackson. I was a Michael Jackson fan from the beginning when he was just a little kid, and even then he was awesome. I’ve tried to follow him, and as far as I’m concerned, if the subject is popular music, Michael Jackson doesn’t even belong in that group. He belongs in a group like me or a group like Sun Ra. He was always making up new ideas.

And I would go even further: In this period, among the things I like the most is march music. I go back to Norfolk, Va., marching band the Spartans, with the pretty ladies and super precision. I think the great historical Black colleges that sprung up after the Civil War have been most valuable, and there should be more respect for this area of creative music. March music today is far-out. I can’t believe how great it is, with precision. They’re not given credit on the level of what these people have put together. Yes, the idea of “popular music” is one way of being able to get a connection to music, which the media and the manipulators have done, and they pushed everybody else out. Young African Americans especially are connected to the hip hop phase of the music and other phases….

And so, going back to your original question about, what do I think about the master musicians: They have always been there, and in many cases they don’t make enough money. It’s the stylists who make the most money. The innovators, every now and then, they make a little money. And when they die, then everybody in the media loves them, because they suddenly can take that material and do what they want to do with it.

To finalize what I’m trying to say, what we call jazz is a sonic continuum. It’s not just about celebration of the past; it’s about the hope of the future. And the hope of the future takes part of the past, takes part of the present-day components from the stylists, and with that [it is] adding the hope of the future, which calls for finding something fresh. If it’s not fresh, it gets stale. Going back to what I first talked about was, the African-American community has stalled. The African-American community has lost a sense of what spirituality is, has lost the experience of the surprise. Without a surprise, I’m not interested.

And so here we are. I’ll be 80 years old in about four months or something like that, and my group is leaving the planet in the beautiful way that the Creator has set up things. And I’m going back looking at what’s happening. What was that? I need to learn more about this before leaving the planet. I want to keep learning, but we are living in a time space that I’ve never seen anything like before in America. I wish and hope that the Creator will help them in whatever way the Creator wants to help them.

Being alive is great and it’s an honor to be alive. Hurray for God! [Mr. Braxton’s voice cracks with emotion] Hurray for the Masters who have made it possible for us to have an experience! Creative music more than any music tries to make an experience, the kind of experience that can help a person in the inside and on the outside. And can help the friendly experiencer find his or her self-realization. I’ll stop there.