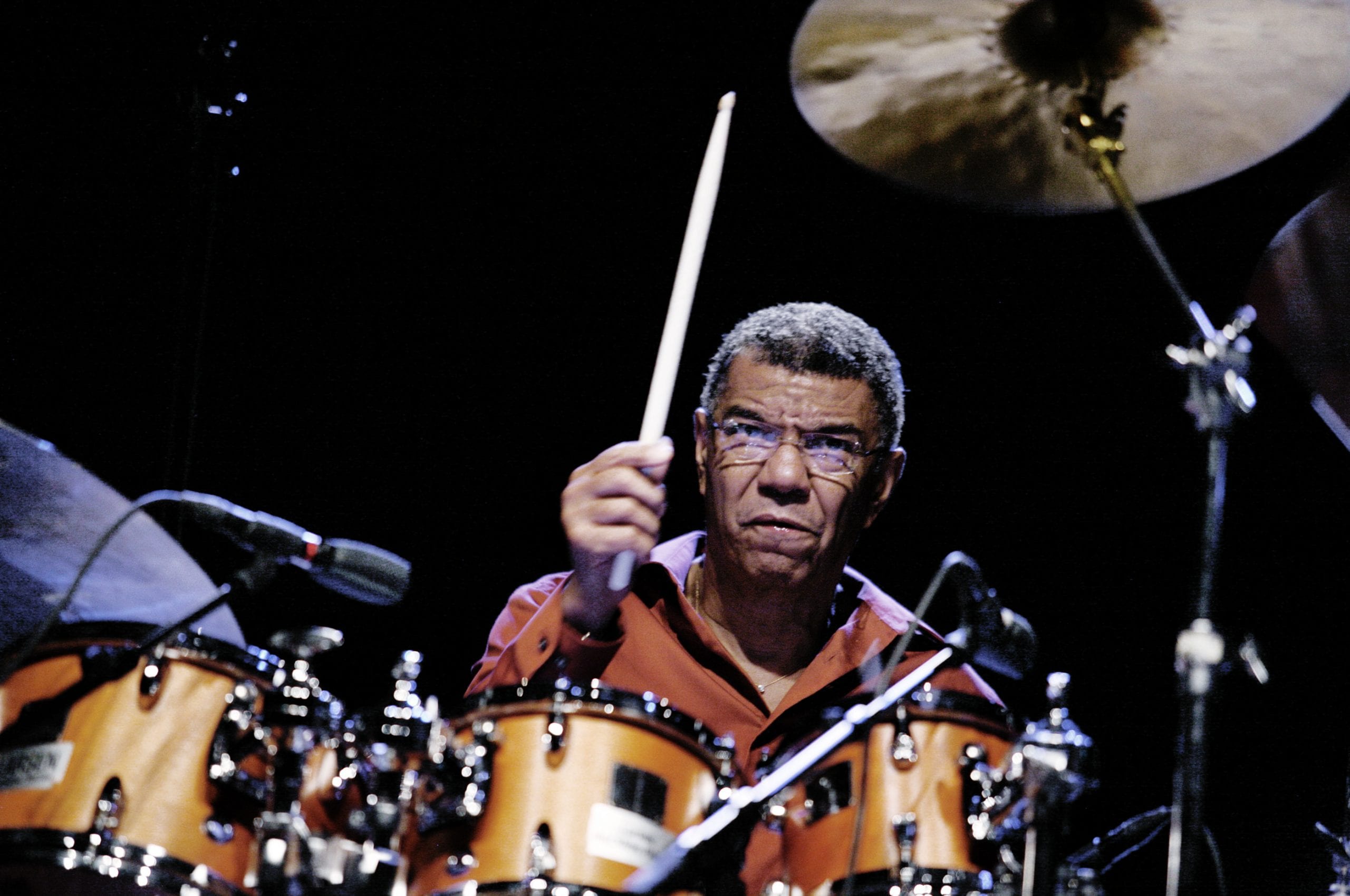

There is a hard line between good and great in jazz. Many cats can play well, with a deep knowledge of the language, but a only a handful can step outside genre lines and be recognized as a true innovator in the field. Jack DeJohnette is one of the greats.

The drummer/ pianist/ composer is widely known for his work on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew, and his extensive partnerships with Keith Jarrett, Dave Holland, and Charles Lloyd. With an inimitable style characterized by his melodious approach to drums and an astute musicality, DeJohnette was the first choice for bandleaders ranging from Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) founder Muhal Richard Abrams to Bill Evans and Freddie Hubbard.

As a bandleader himself, DeJohnette, 72, has yet to decelerate: he’s recorded over 35 projects between 1969 and the present. His most recent release Made In Chicago is a collaboration with AACM heavyweights Abrams, Larry Gray, Roscoe Mitchell and Henry Threadgill. It was recorded live at the 35th Annual Chicago Jazz Festival in Millennium Park. DeJohnette will make an appearance at The Hamilton for the DC Jazz Festival this Saturday with his powerhouse trio. Tenor saxophonist Ravi Coltrane and bassist Matthew Garrison will join him.

DeJohnette gave us a break down of his work with the AACM; time travel and the spiritual watering trough; and how he’s made his entire life a heightened period of creativity.

CapitalBop: You have been working together with key players in the AACM now since your 20s. After 50 years of life, what is it like coming together now?

Jack DeJohnette: First let me clarify the AACM. I wasn’t actually a member of the AACM but I was part of Muhal Richard Abrams Experimental Band, and Roscoe Mitchell and Henry Threadgill were all around at the same time. That was up in ’63 or ’64—just a year before Muhal started the AACM. I’m part of that line of musical thinking, so there is a connection, especially musically. Those connections are fresh; its like we picked up where we left off. Everybody’s been making their own marks and creating their own musical legacies with their directions in music as composers and improvisers. We put that together collectively: the five of us with the addition of incredible composer and bassist Larry Gray, who I worked with in Chicago a few times. It was great to go to Chicago and be honored and play out in Millennium Park to an audience of 11,000 people who really dug the music. It’s been received surprisingly well—I kind of expected it would be. It’s quality music made by music masters who actually defy genres. It gets classified with avant-garde, which some people get confused with free jazz. What we are playing is music—it’s spontaneous improvisation and written composition on a high level. It’s not just fooling around, and because everyone is quite developed as an improviser and composer, when we do improvise, there are always structures and compositions being developed in real time.

CB: Tell me a little bit about your composition Museum of Time. I’m interested in what experiences and energies you were drawing from while writing that piece.

JD: I’m glad you asked. That’s inspired by a series of books written by Jane Roberts called Seth Speaks about the metaphysical aspects and multi-dimensions. One of the books was called the Museum of Time. The concept of time can be looked at like a spiral, and multi-dimensions are going around in a circle counterclockwise, and sometimes you have bleed-through. So sometimes something from another time, the future or the past, bleed through and come into the present. That [DeJohnette’s composition] was a musical interpretation of what that might do. Like if you go somewhere before, and you come to a place you’ve never been to before but yet you say ‘Oh I’ve been here before, this looks familiar to me.’ It might be from a past life that bled through. On one hand you know you’ve never been there before in this life, but it feels very familiar to you.

CB: Many of your albums and projects have a strong meditative component. Is music a primarily spiritual device?

JD: It’s in the eye, ear, and soul of the beholder. The term ‘spiritual’ represents that which is hard to describe, but it’s a feeling of being one with everything. Music and meditation sort of bring us back into the connectedness that we really are in in the first place. We know our environment has kind of taken a beating from our lack of being tuned into nature; it’s karmic stuff that we have to face. People, not only the artists, need to have somewhere—like a spiritual watering trough that they can go to charge up their batteries. That’s what music gives me and the other players like Coltrane, and the guys in my trio Ravi Coltrane and Matthew Garrison.

CB: Do you ever get to a place where you feel like your ideas aren’t as fresh? How do you work through that?

JD: My process is endless. I have a saying—and this is not just for music, this is for everybody. The whole universe is creative; that’s what we are apart of. It’s endless! The many dimensions, like galaxies and stars—it’s awesome! You can think ‘I’m part of that tree, I’m part of that flower.’ We are all part of the same creative consciousness essence. What happens when we become creative after writing a book, painting, or trying to come up with an idea for something that’s got you stuck—I just open myself up and tap into the source and the library of creative consciousness, and there are endless ideas. Just open yourself up to that channel; its like a radio, you just switch the channel. You and universal consciousness kind of work together. We’re always talking,‘Me! Me! Me! I did that!’ Well, not necessarily so. We have angels, guides and energies around us that are always there. When we open up and need help, they’re there to help us. I never worry about running out of ideas. Once I’ve tapped into that space I know I’m going to play something I’ll never play again. We all have that capacity.

CB: Tell me about choosing Ravi Coltrane and Matt Garrison as partners in this trio.

JD: They’re like family because I worked with Ravi’s mom and dad in the mid 60s. It was John [Coltrane], Alice [Coltrane], Pharaoh Sanders, Rashied Ali and Jimmy Garrison on bass. Matthew actually lived with us when he was a teenager. He finished high school studies here and then went on to Berklee, so he’s like a godchild. Then I worked with Ravi and Alice after John passed, so there’s a big family connection. There’s also a spiritual connection between the three of us. I put this trio together about 20 years ago when we played a concert at the Brooklyn Museum on a Sunday afternoon. That was the first time we got together, and then I got the idea for us to get together again, and we’ve been doing that for a couple of years. We’ll be in the studio recording an album for ESM records in October, and that’ll be coming out April of next year.

CB: Sometimes it seems as though the progression of jazz in academia has weakened the community element of workshops, loft shows, and other instances where people came together simply to play and learn from each other. Do you feel like the increase of jazz in school is leading to a demise of jazz in the streets?

JD: It’s kind of a catch 22. I think it’s harder now for young musicians to make a living at it. The problem is that there are more practitioners than there is work. It’s like everything else; you have to learn how to improvise. You have to adapt to the changes. One has to think, ‘how do I see myself in music? As an innovator? As a free musician, manager or entrepreneur?’ You have to be able to wear a few hats.

You’ve got to do social networking, you’ve got to figure out how to get people to come to your site, and find venues where you have to work for the door to build up your visibility. There aren’t a lot of main groups that musicians can get apprenticeships with like there were 20 years ago. How do you survive as an artist in this overcrowded world? Music should be a joy, as well as what you do for a living, as well as your art. But it’s easier said than done.

CB: Did you ever think that you were going to be Jack DeJohnette, one of the world’s greatest drummers? Did you see yourself at the beginning of your trajectory getting to the level that you’re at now?

JD: I had a strong sense of that, but I also came up at a time when you had to learn from the streets, listen to records, and go into clubs. I put myself in challenging musical situations with players that helped me grow to my fullest potential. When I was a teenager, I looked out the window and said ‘this is what I want to do. I’m going to see the world and I’m rich in creativity.’ And I put myself in those positions that best served the level of my creativity. I came to New York and got to play. Everybody came to New York to network with the best musicians at that time, and that’s what I did. I soaked it up with people like Coltrane, Miles [Davis], Sonny Rollins, Bill Evans, Charles Lloyd, Betty Carter, Abbey Lincoln, and Jackie McLean. That’s where I felt I was supposed to be.

CB: For young musicians who are on the fence about whether this lifestyle is really for them, is there a rights of passage or a point of assurance that allows musicians to realize themselves?

JD: Sometimes you don’t choose a profession; it chooses you. Once you get bitten by that bug nothing’s going to stop you. You just find a way. You ask the universe for guidance in that. You don’t always get what you expected but it doesn’t hurt to ask for help. Ask the universe and ask people around, or have a vision. Don’t see limitations! Look outside and not in the obvious places. You have to create the environment. Sometimes the environment doesn’t exist and you have to create it. Like that saying from Field of Dreams ‘Build it and they will come.’ But you have to be tenacious; there are no guarantees. Sometimes you might get weary and say, ‘I’m gonna do something else and come back to it.’ But stay with it. For me, it never occurred to me that I would want to do anything else but play music.

Join the Conversation →