Butch Warren played on classic recordings by Thelonious Monk, Herbie Hancock and Dexter Gordon. Courtesy Antoine Sanfuentes

by Giovanni Russonello

Editorial board

Butch Warren, a bassist and D.C. native who lent a flexible muscularity to numerous classic albums in the 1960s, then spent decades in reclusion before reappearing in his final years to become a quiet standard-bearer on the District’s jazz scene, died on Saturday. He was 74.

The cause was lung cancer, his daughter, Sharon, told the Washington Post.

A 19-year-old Warren was standing along the wall at Bohemian Caverns one night in the late 1950s when Kenny Dorham’s bassist failed to show up. Warren filled in, and his corpulent sound impressed the trumpet star, who hired him for a six-month gig in New York City.

Appreciation: Lessons from Mr. Warren

Appreciation: Lessons from Mr. WarrenIn this heartfelt remembrance of a poignant moment, D.C. saxophonist Lyle Link examines the importance of Warren’s role as an elder on the local scene.

Warren spent five years there, playing with some of the most illustrious names in jazz and embarking on what seemed poised to be a prodigious career. As the resident bassist for Blue Note Records in 1962 and ’63, he drew thick, felt-tipped underlines of sound on albums by Herbie Hancock, Joe Henderson and Jackie McLean.

He started writing music, too, contributing the radiant “Eric Walks” to a Sonny Clark album, and “The Backbone” to one of Dexter Gordon’s. Thelonious Monk had been casting around between bassists for months when Warren joined his band for a night in 1963. The 23-year-old’s mixture of melodic irony and powerful command won Monk over, as it had Dorham in 1958 and Blue Note’s Alfred Lion in 1961. His surefooted adaptability to Monk’s rhythmic illogic stands out on Miles and Monk at Newport and It’s Monk’s Time.

But after a world tour with Monk’s quartet ended in 1964, Warren felt his stability flagging, partly because of what he later called a culture of drug use in the band. Also, Sonny Clark, his close friend, had died of a heroin overdose the previous year; just months later, Warren had watched President John F. Kennedy’s casket creep through the streets of D.C.

Overwhelmed by the death and changes that seemed to be encircling him, he moved back to D.C., stopped playing bass and voluntarily checked in as a mental health patient at St. Elizabeths Hospital. He was diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic and given electroshock treatments. “I didn’t get locked up and put in jail; I volunteered to go in,” he said in a 2012 interview. But as it turned out, “that was like jail.”

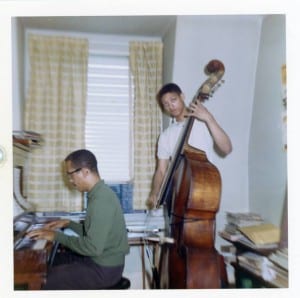

Warren, right, jams with the pianist Cedar Walton, c. 1960s. Courtesy Antoine Sanfuentes

Warren strived to emulate another of Ellington’s bassists, the great Jimmy Blanton, whose cavernous sound on records always captivated him. He spent a stint at junior college in South Carolina, then moved back to the District in the late 1950s, where he began playing consistently, and eventually moved to New York at Dorham’s encouragement. After his five years of distinguished service on the national jazz scene, he returned to D.C. and checked into St. Elizabeths in 1964. When he emerged the next year, he was dedicated to maintaining a low profile and searching for balance.

In 1967 Warren led the house band on Today with Inga, a morning talk show on D.C.’s Channel 4, but within the year he’d quit. “No matter what guest came down, no mater how good they were, because he was in the house band, he’d always steal the show,” the pianist Peter Edelman, a pianist who played with Warren since the 1980s, remembers hearing from someone who was involved.

During the 1970s Warren alternated between playing at local venues and other forms of labor – repairing radios, or mopping floors. He spent a few more years at St. Elizabeths, then found surer footing for a few years and moved into a row house in Adams Morgan. Much of the power in his sound was still preserved. When the local guitarist and bassist Bill “Magic Lavender” Bey first met Warren at Harold’s Rogue & Jar Club, “I had no idea he was a musician. We just spoke for a while,” Bey said. Then, when Warren came to the bandstand, he realized what kind of musician this man was. “I had heard of Butch Warren earlier, so when I saw him play and I saw his fingering I said, ‘This has got to be Butch Warren.’ He played so much on that bow – when they played some fast stuff, it was just like he was sawing the bass in half. It was so much, I actually hid my guitar.”

But for the next two decades Warren struggled to maintain a steady income or a home, and often elected not to take the Thorazine he was prescribed, because of its side effects. His friends sometimes came across him roaming the street; Edelman remembered that Warren passed one winter in the early 2000s in an abandoned building on Bladensburg Road, without food or blankets.

If not for the power of the recorded note, this period of artistic slumber might threaten to overtake Warren’s work in collective memory. In articles and fans’ discussions, he has come to fit dangerously well into the mold of a fallen antihero, a delicate artist with no choice but to give himself up to the music. Another way to remember him is through the impact of his sheer presence on the local scene during his final years, when he appeared live more consistently, although his solos were short and his words were few.

“With his credentials, to be able to listen to Butch’s concept was invaluable,” Edelman said. “His time feel, his approach harmonically and melodically, the way he shaped his solos, the way he phrased ideas, just his whole demeanor on the bandstand. And his focus.”

Laconic and retiring, Warren often seemed to be lost in thought when he appeared at clubs, and preferred to keep a reserve bassist on hand during gigs so that they could switch off on duties. But whenever he touched the bass, his sureness of cadence and fleecy power provided an awakening.

When he did speak it was typically in one-sentence phrases, often apothegms. The saxophonist Lyle Link recalled in a personal remembrance that a well-placed line from Warren helped alter his approach: “It’s not about playing a bunch of notes,” the bassist said to Link onstage at a jam session in the 1990s, when the saxophonist was just beginning to play publicly. “Though terse, [those words] were razor sharp and cut right to the bone,” Link wrote. “That night, I was playing with ‘sound and fury but signifying nothing’ and Butch called me on it. And for that I’m thankful.”

Warren, whose two marriages ended in divorce, is survived by a daughter, Sharon.

—

Funeral services are scheduled for 11 a.m. next Tuesday, Oct. 15, at Westminster Presbyterian Church. A viewing will be held one hour prior. Donations to help the family allay the costs of the funeral can be made by visiting butchwarren.com.

There will also be a memorial jam session for Warren from 3 to 6 p.m. on Sunday, Oct. 12. That will also take place at Westminster Presbyterian.

[…] Who | D.C. Musicians ← Obituary | Butch Warren, powerful bassist on classic recordings, dies at 74; cast long shadow… […]