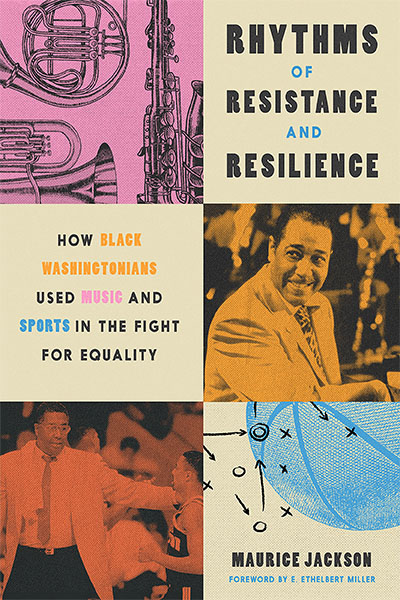

To riff on Fred Moten, the history of Blackness in D.C. is testament to the fact that a sound can and did resist. Historian Maurice Jackson’s Rhythms of Resistance and Resilience: How Black Washingtonians Used Music and Sports in the Fight For Equality is a trove of stories that situate what he calls “Great Black Music” in both the history of the city and the larger history of opposition to racism.

A portion of Jackson’s ongoing research into the people that have shaped Washington, D.C., Rhythms of Resistance and Resilience is a prequel to a larger work, Halfway to Freedom, forthcoming from Duke University Press. In addition to exploring the terrain of sports, Rhythms of Resistance and Resilience examines how D.C.’s music scene — taking place across the city in churches, clubs, institutions, rowhouse conservatories and even prisons — made space for the development of a unique sound that helped create the conditions for transformation.

The study primarily gives stories of influential figures in the city’s musical history, such as Marian Anderson, Louis Armstrong and the Turkish Ertegun brothers, as well as the role that teachers such as John Malachi and Calvin Jones played in training the talent that continues to shape D.C.’s music. Through these individual stories, the book’s major takeaway may be just how central space and place are to making sound.

And if D.C. has a sound, it is one that fights back.

Rhythms of Resistance and Resilience was released this month via Georgetown University Press. CapitalBop spoke with Jackson about his approach to telling these stories and what makes D.C. such a vibrant site for exploring the history of music.

CapitalBop: I want to begin with your approach. One of the most interesting elements of the book is the personal touch, which is sometimes an approach that historians might hesitate to deploy. But one gets a sense of who you are as a person who has experienced what D.C.’s cultural scene has meant. While there is the archival, there’s also a great deal of the personal. Can you talk about your journey towards coming to D.C. and why the city has become such an important space for you as a person, as an organizer, and then as a historian?

Maurice Jackson: I grew up in Newport News, Va. It was sort of an all-Black enclave…. My stepfather had been an old Army Air Force band member. So people came through all the time coming by the house. They had the Hampton Jazz Festival. There was always music around.

Then I spent a formative time with my grandmother in Alabama after my folks split up. She had an old Victrola and she had all these old 78s: there was Paul Whiteman, there was [Duke] Ellington, there was Count Basie…. And in the South, you also listen to country-western music and church music. So all of it sort of comes together.

Well, I ended up in Washington. I’d gone off to Fisk University, and I really didn’t like it. So I dropped out and went to work in a shipyard as a longshoreman for a couple of years. Went back to Fisk, didn’t like it. And [then I] had a chance to come to Washington on an internship working with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

They had an office right there with all the people there, the Tenants Workers Union. But up under the building was something called Dupont Circle Records. And in those days you could go in a record shop and just read for hours. And I would just go in, and I had become infatuated with Coltrane, but especially with Ornette Coleman. That was my man. I started really getting to a deep study of Ornette and Albert Ayler and people like that. And just by accident, I became very close — like a brother to me for 30-some years — with Charlie Haden, who was [Coleman’s] bass player. And whenever he’d come I’d go and see him and play and we mainly talked about not so much music, but about politics and the role of music in politics.

And so it sort of came together. In those days they had a couple of nice places you could go. Of course, Blues Alley was very expensive, but you could go to One Step Down, which was only a couple of blocks up the street, and that’s where I first met Charlie. Woodie’s Hilltop Pub was right across from Howard. d.c. space, which had the avant-garde, and Marion Brown, and people like that was right down on 7th Street, right by the old Lansburgh Building.…

I didn’t want to stay in Washington. I wanted to get to New York.… But I ended up here. I got very active in politics, got married and just stayed. And I’ve seen the changes the city has made.

CB: The book focuses on both music and sports to engage Black life in the city. What is interesting is that we get a lot of short narratives on key figures. Everyone from Joseph Douglass to Shirley Horn, both of whom have important connections to the music known as jazz. Why did you choose to deploy short-form biography as a way to engage these modes of resistance and resilience?

MJ: Well, you want people to read. And I’d read all the biographies. Now there’s not much written on, let’s say, Shirley Horn. Or John Malachi. The great Karl Marx said of Friedrich Engels, “His beauty is that he could take complicated things and mold them into things that could be read.” Marx also said that “it’s not the consciousness of people that determines their being, it is their being that determines their consciousness.”

I wanted to understand how, in fact, these people who made such a role in Washington decide to stay here. What made them do this? What’s the conditions? And it was the social conditions. Because they had families they did not want to necessarily leave. The chance to make it is very, very slim. So most did leave. The great ones. Ellington left. James Reese Europe left, Charlie Rouse. But [other] musicians had to stay here and make a living, but also to play a role in their society.

We look back and forth at those who did [stay in D.C.] Shirley Horn, a prodigy trained at Howard. And when she goes there, of course, Howard does not allow people to play [jazz]…. You play some jazz, you’re getting thrown out. And so she went there. She’s classically trained, but she took her jazz there.

Buck Hill, a working man. You know the old [saying]: “There’s always work in the post office.” And he got a job in the Post Office…. And so what happened? Buck walked the beat. And as he walked, he could keep his health, meet people, and then play at night.

The great Reuben Brown, who I used to see down at One Step Down. And then, of course, other people are trained in D.C. Geri Allen, who studied with John Malachi. And John Malachi, [who] played with Ella Fitzgerald and Keter Betts, and so many [others].

What I saw was that these were the people who made men and women’s souls. These were the people who could use the music to better their lives, but also to better the lives of others.

CB: There’s also this focus on how biography intersects with place and space. Almost every time you mention a jazz venue, you include its former address, almost to suggest that we not forget what these neighborhoods used to hold. Can say more about the small, less formal institutions — like the Modern School of Music, which you discuss — and how musicians today, such as Jason Moran, keep their influence on the city alive?

MJ: We don’t know a lot about [the Modern School of Music], and that’s one of the places that we need to know more [about]. What we know is that Frank Wess studied there, that he’d gone there after he came out the military. He came here seeking to study particular music, to study the formation of music, the classical and also the arithmetic aspect of it. And that he got it.

It was not a big school. It was a local place where people just go in. It was just one of those unique small places that we need to know more about, that did not last very long at all. [Those kinds of spaces] popped up all over. It’s something that I need to know more about. But I learned about it by reading about Frank Wess.

Jason [Moran] is different than a lot of other musicians. A lot of musicians in the old days, they would come [to D.C.], and then after, they hit the clubs. Two people brought the tradition back. Wynton Marsalis, whenever he goes to a town, he’s going to go to that little place, at least when he got started. Wynton would leave the Kennedy Center and go looking for the places. And in D.C. at the time, they had these little loft clubs and people just go and jam all night…. You had little spaces like d.c. space and places like that. But they sort of closed down for a while.

Jason is [also] doing that, and he does that in all the towns he goes to. And then he discusses the local musicians. So, you see, with the latest piece he did with James Reese Europe, he recruited Brian Settles and he recruited Reginald Cyntje…. So he’s bringing in local, very talented players, who could play anywhere. And he gets this by visiting those spaces.

CB: You used the term Great Black Music to thread the music of everyone from Will Marion Cook through Duke Ellington all the way to Marvin Gaye. There have been many attempts to label regional sounds. What do you think of a D.C. sound? And how is it connected to the larger world of Great Black Music?

MJ: You had Marvin Gaye, who would probably be considered the greatest popular musician to come out of the city. Then you had — at Howard — Melvin Lindsey and the Quiet Storm, and things like that during that period.

The greats came. Leadbelly came and left his mark. Others came, left their marks. As most cities were, it was all big bands up until the ‘30’s and ‘40’s. So it was Duke [Ellington] coming through.

The local sound today is defined by Chuck Brown and by a different form of the combination of hip-hop and rap. Understand that all the great musicians left [D.C.] before they [formed] their distinct sounds. Sonny Stitt, the next Charlie Parker. He left. He came back later on. Butch Warren, who played with [Thelonious] Monk. They left, then they came back … with a particular jazz sound.

What you have found though, D.C. is known for certain things. For example, D.C. is known for its great bassists. And it’s got Michael Bowie, Corcoran Holt, Ben Williams, the Carters (The Carter Trio), Luke Stewart [and] of course Keter Betts. It had been saxophones; now, I think it’s the bass. It’s something about the bass in this particular city.

CB: Do you think it’s connected to the music education programs here?

MJ: Definitely a lot of them come out of Duke Ellington School of the Arts. I remember some guys who had groups, they would get very upset because Davey Yarborough didn’t want his guys playing with other bands — he wanted them to get the foundational music right there. And so some people got upset that he didn’t let them go out and play with everyone. Davey knew what he was doing. He wanted them to get that good foundation. And when they got that foundation, boom!

Join the Conversation →