The past 10 years or so will likely be remembered as a breakthrough moment for West African pop music in the United States. Collaborations with superstars such as Drake and Beyoncé have no doubt helped raise the profile of artists like Wizkid and Burna Boy, but those artists now stand as recognizable stars on their own. Still, the biggest shift of late has not been in terms of African music’s popularity on this side of the world, but rather its accessibility. In truth, there has been immense interest in African music in the United States — in one form or another — for about as long as this country has existed. But this interest was rarely reflected on record-store shelves.

A key exception to this dynamic was at the African Music Gallery, a store that operated in Washington, D.C., in the 1980s and ’90s. It was not just a record shop, but rather a cultural institution of great importance to D.C.’s African-expat community, as well as an indie record label. Looked at in retrospect, the AMG played an important role in pointing to new ways that African music could be distributed in the United States, and made more widely accessible.

The African Music Gallery was both the business and the passion project of a man named Ibrahim Bah, who had moved to D.C. from his native Sierra Leone in 1974, on the advice of a relative. “I’ve been around music all my life, practically,” Bah said in a recent interview. In his new home, Bah’s longtime love for finding records persisted, and became a source of comfort. “You get nostalgic when you’re away from home,” he said. At this stage, African music wasn’t easily accessible in the States. When Bah first moved to the city, there was one record store in the D.C. area selling African music, but the management’s knowledge of the music was “not strong,” he said.

“They were held back in the sense that since they did not grow up on the continent itself, it’s hard for them to know what was happening,” he said. “There would be records in circulation that were very popular [in Africa] that would never get international recognition or get on vinyl. And so if you are not on the continent, or have connections on the continent, you will miss those records.”

This motivated Bah to begin importing records and selling them out of his apartment, a process that involved a dense network of phone calls and dead-ends. Today, in a search-engine world, it seems like unimaginably tedious work. Still, this venture proved successful enough that, in 1982, Bah was able to move into a full-fledged storefront in Northwest D.C., first on Florida Avenue and then on U Street. He said the city’s Black community, which attracts immigrants from across the African continent, proved especially welcoming.

“I think the D.C. community was unique,” Bah said. “Being in D.C., there are lots and lots of Africans there who were in my shoes, wanting to hear this music, and could not find it. And I was not only selling the vinyl. Because I was in touch with the artists, I had a wealth of information to offer some of these customers. And that kind of information, it was hard to come by in those days.”

Bah’s relationship with these artists was not one-sided, either. Legendary musicians such as Samba Mapangkala, A.B. Crentsil (leader of the Sweet Talks) and even King Sunny Ade made sure to stop by his store when they were in the D.C. area. One musician, named Tete Fredo, told CapitalBop that in D.C., “if you wanted to meet other Africans, there were two places. You used to have the Club Kilimanjaro, and you used to have African Music Gallery, Saturday morning. If you wanted to meet someone, you’d just go to the African Music Gallery, because everybody was coming there every Saturday to buy records.”

Buoyed by his early success, Bah soon expanded his activities. He hosted a radio show on WDCU 90.1 FM, titled The African Connection, and in 1985 he began producing records by Soukous legends such as Tabu Ley Rouchereau and Syran Mbenza and releasing them on his African Music Gallery record label. “When we’re talking about African music in the United States, he was the only one who was producing it,” Fredo said.

Soon, Bah began using his connections with African musicians to bring them to the area for live performances. Fredo himself first came to D.C., where he now lives, while on a U.S. tour with the Soukous supergroup The Four Stars (or Les Quatre Étoiles). “Ibrahim was the first person to invite musicians to the States,” he said, “and because of him we have all those groups there in the States. You plant the seeds, a couple years later you’re gonna have the fruit.”

When I asked Bah how he ended up expanding into tour management, he replied humbly: “It just happened, really. I figured there was a market for them, and that the people who had been listening to these records may have wanted to hear and see these artists perform live. So I tried and brought many of them to the U.S. Some did successful tours, and some did so-so tours. But for me, it was all a learning experience.” Indeed, the many projects Bah partook of during his time in D.C. seem less like business ventures and more like the natural progression of a lifelong passion for music.

During his childhood, records often did not include images of the artists who actually made them, instead opting for images of “nature or animals or something,” he said. In fact, Bah could recall his first time actually seeing a physical photo of an artist he loved. “I was with my teenage friends, we heard that an artist who went to Ivory Coast apparently had gotten a newspaper with a picture of this guitarist from the Congo by the name of Bavon Marie Marie,” he said. “And when he got to town, word got around that he had a picture of these guys that we’d never seen. We’d heard their music over and over and over, and we just wanted to know what this guy looked like. Believe me, we woke up around about six in the morning, finding a way how we can get to whoever has the picture. We made our way there around about 8:00, and he took out a newspaper and we saw this picture. Man, we were like kids in a candy store, just looking at these guys felt so good.”

With the African Music Gallery, Bah brought that joy of connecting with the music he loved to the D.C community, helping to bring the music, the musicians and the culture of African music into the city’s everyday life.

In 1992, after ten years, the African Music Gallery shut its doors. “CDs were coming into vogue, and the market was simply changing,” Bah said. “So it was time to get out of the vinyl business, and then I just decided to pack up. The burning fire that was in me when I started out was no longer there. So I thought it was time to give up.” More recently, Bah moved back to Sierra Leone, where he said he is working to start a radio station, Rumba FM; he expects to be broadcasting on the air and on the internet by this summer.

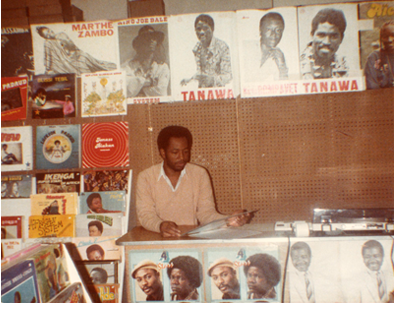

African Music Gallery. Courtesy Ibrahim BahWhen I initially began researching the African Music Gallery’s history, I struggled to find much information on Bah outside of one Washington Post feature and a couple of academic articles written by Gary Stewart, all of which were published prior to the store’s closure. However, this lack of information belies just how important the African Music Gallery was. Bah’s business showed that the distribution of African music could, in fact, be determined by the interests of African diasporic communities, not just the whims of white record executives looking for the next international superstar, à la Miriam Makeba or Fela Kuti. It was a space in which members of the African international community could socialize and enjoy their music on their own terms, without any middleman determining how they could do so.

While the most well-documented people in D.C. are those in positions in power, the actual history of the city, which lies in the people, places and communities that take root here over time, can be much more difficult to trace. But as these communities become displaced, the history is in danger of displacement as well.

When I asked Bah if the internet had changed the dynamic between African musicians and Westerners that he had described earlier, he responded immediately. “Definitely, because now most music from Africa you can access on the internet, so it’s easier that way for the fans to get what they like directly,” he said. “And so, in the end, they determine what sells. It’s not a producer who says, ‘Well, this guy speaks in this or that language, so I don’t think he’s gonna sell.’ No, that middleman is out.” Untangling the positive and negative impact that the internet has had on African music (or anything, for the matter) is much too complicated a task to accomplish in one paragraph, but it has undeniably made African music more accessible, helping to push it into the global mainstream and enabling communities to organize themselves around the many, vastly different forms of African music.

“Someone asked me way back, I guess, during the days of the African Music Gallery: ‘What do you foresee in terms of the growth of African music?’” Bah recalled. “I don’t know if I was smart or just lucky; what I said was, ‘I believe African music will rise to the point where it will just be at par with the rest of popular music.’ And that’s where it is today, with Afrobeats and all. But there are yet other forms of music to be discovered in Africa. And there are a lot of styles, you know, because when you think of it, every ethnic group in Africa has a unique musical form, sometimes a variety of forms. So all that is still to be explored.”

Join the Conversation →