For much of the 20th century, U Street was known as “Black Broadway,” a mecca of Black cultural life in the United States — perhaps second only to Harlem. The corridor was home to 300 Black-owned businesses, including numerous jazz clubs, dance halls, nightclubs and theaters; 100 churches; and the crown jewel, Howard University, a center of African-American intellectual life since the Reconstruction era.

That history is being celebrated this week at the seventh annual D.C. Funk Parade, which is taking place virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with performers from across the District’s arts scene paying tribute to the corridor.

Events like the Funk Parade have become a part of the evolving story of Black Broadway — but, as local author and journalist Briana Thomas told CapitalBop in a recent phone interview, “We can do a lot more than just sing and dance.”

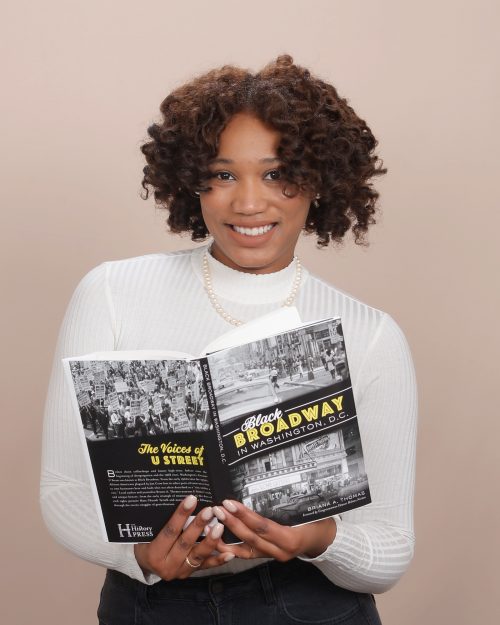

Thomas, who was born in Laurel, Md., and got her master’s degree in journalism from the University of Maryland, College Park, recently published a book, Black Broadway in Washington, D.C., now out on History Press, that seeks to expand and deepen our collective memory of U Street. In it, Thomas traces the whole history of the strip, from the 1800s through today. She explores how the corridor took shape geographically and politically as well as the economic, social and intellectual forces that helped shape everything from Duke Ellington’s future to the NAACP to Howard University and the esteemed Paul Lawrence Dunbar High School. She also focuses on the figures, especially the women, who were responsible for that formation.

I talked with Thomas about all this by phone recently, and about how she would hope to see U Street’s history carried forward in the coming years. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

CapitalBop: I know you’re from the area and grew up in Laurel, Maryland. Did you inherit any memories or stories of “Black Broadway?”

Briana Thomas: Oh yes, most definitely! My grandmother actually moved to Washington, D.C., from Suffolk, Va., around the ’40s or the ’50s, which was not uncommon for black women during that time. Actually, in the book I go through a full chapter about women and live-in servants and how they didn’t really have opportunities. She was the first person to share her U St. memories with me. And when I started researching this project for Washingtonian magazine, she was one of the first people I talked to because I remembered when she took me to Ben’s Chili Bowl to get my half-smoke, and took me to the Howard Theater. She spent a lot of time on U Street when she was in her early 20s because that’s where everyone came during that time to work and to play and to have a good time. So, she would go see movies at the Lincoln Theater, go to the Republic Theater, Howard Theater. She told me all about how she’d go to see Redd Foxx and Moms Mabley, the comedians. And during her time, she would go to what was known as the Caves — the Caverns, Bohemian Caverns.

CB: How did that Washingtonian article come about?

BT: I worked there in 2016, while I was a graduate student at the University of Maryland, College Park. I took a summer fellowship at Washingtonian, and I didn’t pitch the story; it was assigned. Kristen Hinman, one of the features editors, gave it to me. So when I said yes and got the assignment, I went, “Wait a second, I know this! I know U Street and I know the history.” It started off not just as talking to my grandmother, but I went back to the first person that I knew when I went on a “U Street Tour” — maybe in high school — and that was Dr. Bernard Demczuk. He wrote the epilogue to my book and he’s the official “Ben’s Chili Bowl Historian.”

I started sitting with him at Ben’s and we took a whole ‘nother tour, like the tour I had taken back when I was in high school, and it really grew from there. What was special at the time was that my Washingtonian article was specifically focused on the businesses that were remaining on U Street from the “Black Broadway” era. There’s only three left: Ben’s Chili Bowl, Industrial Savings Bank and then Lee’s Flower and Card Shop. It was more-so a photo-driven story, taking the community narratives and showing the imagery of that day. And then, after it published, a book publisher saw it and that’s how the book came about.

‘When I said yes and got the assignment, I went, “Wait a second, I know this! I know U Street and I know the history.'”

—Briana Thomas

CB: It seems like the direction you chose to go in was not just describing “Black Broadway” and that history specifically, but discussing how we got there and why it was the center of Black intellectual, social and public life for a lot of the last 150 years. Can you talk about how you chose to go in that direction?

BT: Actually, I was on a panel and it was called “If U Street Could Talk.” My answer to that is always, “If U Street could talk and if U Street had a voice, U Street would say, ‘Tell my full story.'” When I sat down to write the book, I didn’t know if it would be able to give U Street’s full voice. The back of my book is called “Voices of U Street” because I actually wanted to title it that, but my editor was like, “Go with ‘Black Broadway.” So! [Laughs.] I really wanted to tell and narrate the entire history, because you can’t talk about Duke Ellington before you talk about Frederick Douglass, right? And you can’t really get the full scope of what came to be a place where there were 300 Black-owned businesses and 100 Black churches and all of these Black-owned nightclubs and after-hours spots, without walking through D.C. being a slave-holding city and housing one of the largest slave markets. And then I didn’t want to also talk about the golden years of “Black Broadway,” but not mention the fact that U Street doesn’t look like that anymore: The population is not majority Black; it’s no longer a time when you have a Black-owned business on every corner. That’s what really made me go in that direction of, “If you’re gonna tell a story, let’s tell the full story.”

CB: Is there anything that stood out to you during your research? Any narratives that surprised you as you sought to weave together the “full story” of U Street?

BT: Definitely, and one that comes up fresh in my mind of what surprised me was specifically: People know “Black Broadway,” and it got its name because of its music, but behind the music was so much activism and Black education and achievement and innovation, which I thought was so important to highlight. And also, Black wealth. I think that was one of the things that surprised me in researching, was how much – not just resilience – but how much wealth and funding and the economic status of Black people at the time, even in D.C. as a whole. By 1901, according to the Union League Directory, there were 1,000 Black-owned businesses in Washington, D.C. That’s very surprising because you’re talking about being emancipated from slavery, what, not even a full 40 years prior, and already 1,000 Black-owned businesses? So those are the kind of history things that are shocking to me that are very important to highlight?

CB: Is that why you focused on the music and nightlife aspect and more on the business and activism — because those are the stories that have been told less over time?

BT: Yes! That’s exactly it. And I’ve done a lot of interviews and you’re the first person to notice that! [Laughs.] But yes. The reason being, not to sound blunt or anything, but the reality is that Black people have always been known and highlighted and celebrated for being pieces and props of entertainment. And not that we aren’t great entertainers and should be highlighted and celebrated for it but we can do a lot more than just sing and dance. That was something that I really wanted to show when I was traveling this history of U Street and the history of “Black Broadway” specifically is that there would not have been some of these [institutions], like True Reformer’s Hall. They had cabarets and dance halls but the building itself was owned by a Black benevolent society and it was funded with $60,000 and built by the first registered Black architect in the city. So yes, you have entertainment, yes you have nightlife, but let’s take a look at what came, not just before, but what’s really pushing the reason why we can have fun.

CB: The only other U St. history book I know if is Blair Ruble’s. Is yours the first Black-authored history of U Street?

BT: A lot of other books about D.C. are written by, No. 1, people much older than myself, and also white people — and specifically white men. So, there is something to be said about me being a Black author and a Black woman author, and a millennial at that, to really cover the history of U Street; but I’m definitely not the only one. Maurice Jackson and Blair Ruble edited DC Jazz.

Briana Thomas. Courtesy Briana Thomas

CB: Yes! I thought about Maurice Jackson when you said, “You can’t talk about Ellington without talking about Frederick Douglass,” because he said something similar about how Ellington was really influenced by Rayford Logan, the great historian at Howard. It goes to your point about the intellectual, activist and economic aspects of U Street being fundamental to everything else that come up around it.

BT: Yeah, definitely, definitely. The first world-renowned opera singer Madame Lillian Evanti went to school at Howard University. So as you mentioned and as my book highlights, music is so important and so special and so empowering, so I do not want to downplay that aspect at all. But it is also not all that encompass the city, U Street and Black people as a culture as well. There is education and entrepreneurship as well; and I think to be a musician you need a piece of entrepreneurship.

CB: Going back to this idea of being a Black woman millennial author in this space, were there specific gaps in the history you saw written before that you wanted to fill in?

BT: I do think what my book did differently — in looking at other books that journaled U Street or D.C. — although there was no U Street pre-Civil War, I did really want to start at slavery because I wanted to start at the actual formation of the city, and how U Street became a corridor itself. I think that’s something that makes my book span out. Another piece, coming from my own age, is I do have the most recent book. So, I was able to end the book with a chapter specifically talking about gentrification and the #DontMuteDC protests and Moechella and things like that, that really speak to my generation, and preserving the history and preserving Black music in D.C.

And then another thing I wanted to do was highlight women, which I don’t think can be glazed over when you read history books in general! I did want to make sure I include women in the history; that’s why I have a whole subsection for Mary Church Terrell, whose house is still located in LeDroit Park. Her husband was Robert Terrell, who was the first Black federal judge. She was a prime activist; she was one of the founding members of the NAACP, which is special to note because a lot of times — especially when you’re talking about the civil rights movement — Black women were behind it, or actually beside it. They were pretty much overlooked when a lot of the history was then journaled. Those were things I wanted to shine a light on, women specifically.

CB: You touched on #Don’tMuteDC and gentrification, which are obviously things we care about a lot at CapitalBop. Let’s say in 10 years you write another chapter to cover the further history of U Street. What would you hope to chronicle in that?

BT: That’s a great question. I think what I would hope to be able to chronicle is a U Street where there are a lot of new people and it is diverse and it is safe — because that’s a big piece, right? The reality of U Street is that, even in some of the later period when this was Chocolate City, nobody wanted to be there. There was a crack epidemic, it was not safe. But once the city got cleaned up and the city was safe, the question is, “Who do we clean the city up for?” Because a lot of the people who built the history can no longer afford to live in what they built.

No. 1, I would like to be able to say the name of Vice President Kamala Harris, who is the first woman in the White House and a Howard University graduate! There are a lot of firsts still taking place on U Street. Dunbar High School was the first high school to admit Black students in the nation, but now, in 2021, we have the first Black woman vice president. And then I would hope that the population and the numbers and the property taxes — and the things that we’re seeing, like 150-year-old churches like Lincoln Congressional having to shut their doors because their parishioners can’t afford to live in the area any longer — those are kinds of things I would like to see reversed. I would like to see more Black businesses come to U Street and I would like the businesses that are on U Street be able to stay.

And I would like to see the music halls and the venues and things like that get the proper funding. Save Our Stages is so important now because what’s left of U Street is also closing.

CB: I was going to say, how much would that last chapter of the book have changed if you had written it during Covid times?

BT: Yeah, right? I think about that often. I literally finished my manuscript right before the world shut down in March 2020. I don’t think we’ve fully processed the pandemic, now a year later. No one is going to be able to process this for some time to come because right now we’re all living through it and kind of in survival mode. So from a journalist’s standpoint and from a historic standpoint, it would be quite interesting to see. I had U Street Music Hall as one of the venues still surviving on U Street, and on my final edit I had to take that out. That was kind of tough. It’s like, “Wow! In a matter of months, something that I highlighted and is still here, where you can go see great music and be part of the city’s history and culture and overall vibe, is closed and not coming back.” So, I think it would be very interesting to see U Street post-Covid. I think U Street will survive because that’s what history has told us: that no matter what it is, U Street is going to survive.

Join the Conversation →